Last revised December 2017

No further revisionary updates will be made as a book on this subject is being written.

Authors wanting to cite my work: please wait for the publication of my book.

All conclusions in blog articles are provisionary, and due to more recent research, there may be substantial differences to the final published book, which will not be under a nom de plume.

Introduction

This is an in-depth critical review of Joachim Köhler’s book Wagner’s Hitler - the Prophet and his Disciple. Köhler is a freelance German writer and novelist. All page references are to the English translation of Köhler’s book by Ronald Taylor (hardcover edition).

|

| Joachim Köhler and Adolf Hitler |

|

| The original cover for the German edition sadly demonstrates that the English title of Wagner’s Hitler—The Prophet and His Disciple is neither a joke nor mistranslation |

Title: Wagner’s Hitler – The Prophet and His Disciple

Author: Joachim Köhler

Translated by Ronald Taylor

Original German title: Wagners Hitler – der Prophet und sein Vollstrecker

Publisher: John Wiley & Sons, 2001

English translation: ISBN-13 9780745627106

Original German edition: ISBN-13 9783896670168

Length: 384 pages

Readers who wish to read the book for themselves should note that if your library lacks a copy, then copies can readily be purchased cheaply second hand at Abebooks (readers are strongly discouraged from buying new copies).

I first became aware of Köhler’s book in the late 1990s after it was published in German, well before it appeared in English. I relegated it to the status of a hoax and thought nothing of it. I preferred the journalistic neutrality of Dieter David Scholtz, since checking his claims against readings of Wagner’s primary source texts validated them. So it came as a surprise to discover that the hoax book had been translated into English, whereas none of Dieter David Scholtz’s series of books on Wagner has yet been translated into English. Wagner’s writings show him to have been a democratic socialist revolutionary, who became radicalised by the 1848 revolution into a revolutionary Communist—before moderating his political outlook late in his life to become a European constitutional federalist (anticipating the European Union). He remained an ethnic assimilationist, and a passionate lifelong pacifist throughout his life.

Dieter David Scholtz and Joachim Köhler’s books form a tit-for-tat exchange of prosecution and defence. Köhler has been widely translated into English to give the prosecution free reign over the floor while robbing the defence of a right of reply, while Scholtz’s books have lapsed into obscurity and fallen out of print. The closest to right of reply has come from Milton Brener’s book Richard Wagner and the Jews, which does a fair job despite being hampered by a reliance on unreliable translations by William Ashton Ellis. The book entitled Richard Wagner im Dritten Reich, based on a symposium organised by the legendary Israeli Holocaust historian, Professor Saul Friedländer, in a response to Köhler’s book, contains landmark essays critical of Köhler, amongst them by key historians such as Saul Friedländer and Joachim Fest, but this too has yet to appear in English.

Wagner’s Acquittal

Since the original publication of this review, Köhler has recanted his “petulant prosecution” (as Joachim Fest called it) in an article tellingly entitled Wagner’s Acquittal (of the charge of causing or inciting the Holocaust), published in The Wagner Journal (8, 2, 43–51: July 2014). Köhler has too late conceded to the growing academic literature which has shown that there occurred a political regime change in Bayreuth after Wagner’s death. The new regime, lead by Wagner’s French-born second wife, rewrote history by creating a mythical völkisch Wagner in collaboration with her propagandist henchman, the English-born Houston Chamberlain, while making self-serving claims to be the humble executants of Wagner’s will. This regime change introduced an institutional discontinuity between the Bayreuth of Wagner’s time and that of his heirs. It was a discontinuity that reflected both the changing socio-political milieu of German society, while Wagner’s posthumous fame made millionaires out of his nouveau riche bourgeois family, thus introducing a socio-economic discontinuity to Bayreuth’s infrastructure. Forgotten were the days when Wagner was a struggling avant-garde revolutionary artist, as the family inherited an artistic legacy now worth a fortune, before the 1918 abdication of the Kaiser made ersatz royal family out the Wagner dynasty. Köhler’s polemics had been misdirected at a mythical Wagner concocted after his death, not the historical Wagner who had been deleted from history and willfully overwritten to force the story to conform to the now right-wing ideologies of the newly bourgeois family heirs. Or to quote from Orwell:

The past was erased, the erasure was forgotten, the lie became truth.

George Orwell: 1984

It remains as relevant as ever to critique Köhler’s earlier failed hypothesis so as to appreciate why historians have rejected Köhler’s invention of oversimplified “straight lines” of unbroken lines of continuity where historians find only catastrophic discontinuities and “twisted roads”. Wagner controversies have nothing to do with Wagner at all, but rather constitute attempts to keep alive the discredited theory originating in wartime Kraut-hate propaganda that Germans had always been militaristic, racist, and authoritarian—that they will for forever remain the same—for once a German always a German, this being eternally predestined by German blood and soil, with Wagner forcibly interpreted as the perfectly incontrovertible case in point:

Polemicists always love to assume that there exists an immutable ideological continuity to “The German Mind”, allegedly magnificently exemplified by the incontestable example of Wagner, who proves that Kraut-Think maintained its monolithic, hate-filled imperialist outlook throughout history, untouched by socio-political disruptions and catastrophic discontinuities. Historians reject notions about the linear continuity of a uniform national character, for far from being ideologically homogeneous, societies are inherently divided by explosive class conflict driving cataclysmic historical discontinuities that ensure there can never be such a thing as an immutable and homogeneous “German Mind” other than in the eyes of propagandists.

Hate, Guilt, and Self-Hate

The Israeli historian, Na’ama Sheffi has further written a whole book debunking the Wagner myth entitled The Ring of Myths, and, in an interview about the book with Die Welt, she stated that Wagner is being manipulated in Israel into a symbol of the Shoah to keep alive the myth of the eternally hate-worthy Ur-Kraut of history, just to keep the flame of wartime propagandist emotions burning undiminished—emotions of the kind that scream “we hate the Germans”.

|

| Israeli historian Na’ama Sheffi argues that Wagner is being manipulated into a symbol of the Shoah by those who insist on screaming “we hate the Germans”. |

Likewise, wartime Germans in exile like Thomas Mann and Theodor Adorno, and German-Americans like Otto Tolischus and Peter Viereck, under threat of internment as alien insurgents or spies, chose to frantically bash Wagner so as to “prove” they were not “one of the Hun”. Post-war Germans feeling oppressed by the burden of history today feel alleviated of their guilt through outbursts of hatred towards Wagner by affirming the wartime views of such Germans in exile, “proving” that they too are no longer “one of the Hun”. For too many, history must be seen in terms of either Allied or Nazi war propaganda, thus compelling us to beat on the old drums of hatred and war till the end of time—it seems there must never be a middle path of academic neutrality.

For all the gratuitous seductions of such blindly jingoistic hatred, far more insightful were Friedelind Wagner’s words in a wartime broadcast from America:

“I asked myself how my grandfather Richard Wagner would have acted in my position. Would he have stayed, would he have placed himself at the disposal of the Nazis, would he have lent his name, which is also my name, to their crimes? There can be no doubt: Richard Wagner, who loved freedom and justice even more than he loved music, would have been unable to breathe in Hitler’s Germany. Thus we commemorate a great German, though our country is at war with Germany.”

The Allies were not fighting the spirit of Goethe, Beethoven or Wagner ... but ‘the evils of Hitler and his hopes of world domination’. She was speaking in the spirit of her grandfather, she continued, when she prophesied that the hour of the Nazi’s Götterdämmerung would soon come...

Friedelind Wagner quoted in Eva Rieger: Friedelind Wagner: Richard Wagner’s Rebellious Granddaughter. My emphasis

In undertaking a post-mortem of Köhler’s original thesis, the reader will gain incisive insight into why it would be better if we embraced the fact that it is high time that wartime Wagner myths based on anti-Hun propaganda be allowed to meet their supreme Götterdämmerung.

The Crux of Köhler’s Theory

The crux of Köhler’s book had been that the phenomenon of Hitler could be explained solely on the basis of his devotion to a secret mission to realise his Masterplan “to transform the world into a Wagnerian drama”. Köhler had pronounced with complete certitude that Hitler had pursued no political aim whatsoever beyond that of realising a Grand Plan to transform the world into a super-Wagnerian opera production:

[In] the last radio address [Hitler] gave to the country, in January 1945, he repeated: ‘Only he [probably should read “He” i.e. God] who gave this task can release me from it.’...

The nature of this task was certainly not to pursue a set of political aims, that is, to arrange the political and social realities of the time in the interests of the nation whose Chancellor he was. Reality meant for him the task of transforming the world into a Wagnerian drama...

Köhler, p.270. My emphasis

Von der könne ihn, wie er bei seiner letzten Rundfunksansprache in Januar 1945, »nur der entbinden, der mich dazu berufen hat«.

Nun bestand Hitlers »Aufgabe« gewiß nicht darin, Politik zu machen, sich also mit der Wirklichkeit im Interesse der Nation, deren Kanzler er war, zu arrangieren. Seine Wirklichkeit bestand in der Aufgabe, die Welt in ein Wagner-Theater zu verwandeln...

Joachim Köhler: Wagners Hitler—Der Prophet und sein Vollstrecker. S.384. ISBN 3-442-75547-6. Siedler Verlag, München, 1999

In what Köhler himself now confesses is a failed thesis, Wagner had taken the place of God Himself, as the providential playwright scripting the course of world history, the Grand Puppet Master secretly controlling Hitler from the beyond, manipulating him freely as His beer-hall opera impresario and chief executioner of His divine Will. The National Socialist Party had become an opera company disguised as a political party, one that had transformed the German Imperial Chancellery into an opera house. World War II and the Holocaust had come to be rendered as Hitler’s histrionic enactment of grand opera on the world’s stage. As Wagner’s puppet, Hitler was helpless but to be under the control of his Dark Lord, so that only “[H]e who gave this task” of realising the operatic Masterplan could cut the puppet strings and “release” him from the clutches of Providence.

Merely Acting Under Orders

The transfer of guilt onto a nineteenth-century opera composer had become so total in Köhler’s failed thesis as to have perfectly exculpated Hitler of all responsibility for the Holocaust, as it had reduced Hitler to little more than a hapless puppet forced to execute orders from his God-like Meister.

|

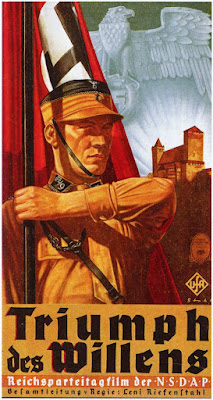

| The Prophet and his Disciple: Köhler exculpates Hitler of his responsibility by transferring guilt for his actions onto a long-dead nineteenth-century opera composer. |

The way Hitler had been portrayed as “acting under orders” from Wagner recalled the way Adolf Eichmann pleaded innocence on the grounds he was merely “acting under orders” from Hitler. Eichmann claimed he was but a mere puppet forced to carry out an extraordinary Führerbefehl (Führer Order) to commit genocide. Historians think that Eichmann made up the self-exculpatory story of a Führer Order since no formal documentary evidence exists for anything like a Führerbefehl ever having been issued. Eichmann had always been acting on his own initiative in ordering mass murder, “working towards the Führer” by anticipating what was expected of him to advance his career.

Köhler sadly realised only too late that he had concocted similar excuses of “acting under orders” on Hitler’s behalf. Köhler had claimed that Hitler (the disciple) had no choice but to act as a puppet controlled by Wagner (the Prophet) to carry out a divinely providential Meisterbefehl (Master Order) emanating directly from the supreme Meister Himself. Köhler had even painted a kitschy scene where the Meisterbefehl to execute the Masterplan of the Final Solution from Wagner was handed down to Hitler through the dying Chamberlain as he lay on his deathbed, thus establishing a direct chain of command going Wagner-Chamberlain-Hitler. Joachim Fest notes that all Köhler had to support this was pure conjecture.

The reaction of other leading historians in this period has been that of similar exasperation. Sir Richard J. Evans wrote in his review of Köhler’s book:

Yet to make Wagner directly responsible for the nazi extermination of the Jews, as Köhler does, is hardly plausible. Köhler achieves this only by erecting dizzying and unstable structures of inference and correspondence, in which phrases and quotations are time and again ripped from their context in the writings or sayings of Hitler and Wagner and made to look as if they are saying the same thing. None of this is remotely persuasive.

Evans: Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 37, No. 1 (Jan., 2002), p. 149. My emphasis.

A History Based on 1940s Political Satire

If National Socialist propaganda had claimed to stand on the shoulders of great German artists and thinkers like Wagner and Luther, Allied war propaganda had exaggerated this for polemico-satirical effect by tipping this on its head in overstating that National Socialism was an operatic movement run on Wagnerian principles, but like the story about Hitler going mad from syphilis contracted during sex with a Jewish rentboy, this has not stopped some humourless bores from taking such delightful witticisms seriously. Authors who repeat such fake stories must keep in mind that Sir Richard J. Evans excoriated Holocaust denier, David Irving, precisely because of his wilful use of fake quotations. It behoves no serious scholar to follow such an example, and write history as farce.

Sir Richard J. Evans has further argued that:

No sensible historian has argued that the total package of Nazism was present in earlier social or political movements or ideologies. What historians have tried to do is to find out where the different parts of Nazi ideology came from.

Evans: Rereading German History. My emphasis.

Least of all, no sensible historian would ever claim that the “total package of Nazism” was present wholesale in the writings of a nineteenth-century opera composer whose “vision” Hitler set out to fulfil in a grand conspiracy veiled from the whole world:

All this took place without his ever revealing the secret of his mission. As, on the one hand, he kept its origin in the Wagnerian world to himself, so, on the other, he laid a veil over its terrible consequences.

Köhler, p.16. My emphasis.

For all of the melodrama in his expression, Köhler failed to provide an explanation for why during the previous fifty years or so prior to his book, none of the legion of historians working on this era had unveiled the “terrible” secret of the operatic origins of Hitler’s “mission”. Nor did Köhler explain why Hitler needed to be so secretive. Was he so ashamed of his grand operatic “mission” that he would conceal it so carefully that it would take over fifty years to unveil his “terrible secret”?

Why would Hitler not stand in front of the roaring crowds to declare that his chief political mission was to “transform the world into a Wagnerian drama”? The answer is that he would no more have conceded to such an accusation from Allied war propaganda than he would have announced before roaring crowds of Party faithful that he had only one testicle. The fake quote oft attributed to Hitler that goes “whoever wants to understand National Socialist Germany must know Wagner” (first found in Tolischus, 1940) was just a satirical concoction of Allied war propaganda trying to make Hitler look ridiculous by insinuating that he ran his nation on operatic principles:

|

| The fake quote “Whoever wants to understand National Socialist Germany must know Wagner” first appeared in a 1940 American propaganda book without a date or primary source citation. The “quote” made up by Tolischus is untranslatable into German, and no original German version or primary source has ever been found. Köhler’s idea of a conspiracy to turn the world into a “super-Wagnerian opera” originates in Allied war propaganda. |

Another author claimed in 1942 that even the economic structure of the German state ran according to operatic theory:

...the internal economic and political structure of Nazi Germany is almost entirely the result of the twentieth century interpretation of Wagner’s theories.

Gregory, 1942

Numerous economists have since studied the economic policies of the National Socialist regime, but none have concluded it was based upon operatic principles. It is difficult to conceive what Wagnerian macroeconomic theory would even look like. Neither Adam Tooze in The Wages of Destruction, Statistics and the German State 1900-1945, nor R.J. Overy in The Nazi Economic Recovery 1932-1938 have uncovered any evidence that the National Socialist economic and political structure was “the result of twentieth-century interpretation of Wagner’s theories”. This, as we will find recurrently, is typical: a bombastic proclamation evincing sweeping certitude is made, but as soon as the evidence-base for this is critically examined, the thesis rapidly disintegrates.

Peter Viereck in 1942 similarly proclaimed extraordinary familiarity with Hitler’s inner psyche, in his Harvard PhD thesis:

Though he knew much of Wagner’s prose by heart [no supportive citation], it is the operas that were the main source of emotion throughout Hitler’s life, a deeper emotion than with any man or woman [no supportive citation].

Viereck: Metapolitics (1942). My bold emphasis.

These amusing proclamations evincing sweeping certainty can only be considered satirical parody based on conjecture. In 1942, virtually no details of Hitler’s personal life were known, as media access was limited even for German journalists, with the existence of Eva Braun being entirely kept secret. Nor were the contents of Hitler’s private library known, which posthumously turned out to have included none of Wagner’s writings, thus explaining why Hitler never once quoted from Wagner’s extensive body of prose writings either in private or in public. There is no evidence of even the slightest familiarity with Wagner’s actual prose writings. However, the certitude of such speculators who make such grossly exaggerated proclamations about Hitler knowing “much of Wagner’s prose by heart” always increases exponentially in inverse proportion to the amount of evidence.

Hermann Rauschning likewise claimed, in another 1940’s propaganda book, proven to be largely fake, that Hitler acknowledged “no forerunner”—“with one exception: Richard Wagner” (Hitler Speaks, 1940). Rausching also depicted Hitler shrieking, pointing into empty space exclaiming “there, there in the corner!”—a line lifted straight from a Guy de Maupassant short story. Given the popular legend associating Wagnerism with madness, it was inevitable that some witty anti-German propagandist would satirise Hitler as a twentieth century King Ludwig II who had been driven mad by his fanatical obsession with Wagnerian opera, causing him to run the “internal economic and political structure” of an entire nation on operatic theories. It is just another one of many colourful wartime rumours alleging that Hitler was stark raving mad. Another similar variant blames the hypnosis used on Hitler during his attack of hysterical blindness after a gas attack in WWI from which he never woke up, alternatively psychodynamic instability induced by a missing testicle, sado-masochism projected onto the world stage (according to the Freudian, Walter C. Langer), or else his mother’s breastfeeding of the infant Adolf as an act of “breast-mouth incest” leaving him “unsuitable for any normal erotic relationship”.

Sir Richard J. Evans astutely notes in the section Was Hitler Ill? in The Third Reich in History and Memory that such entertaining stories were mostly based on rumour and hearsay that circulated around bars during the war:

The problem with many of such speculations is that the evidence they use is unprovable except on the basis of the kind of rumours that circulated round the bars of Europe and the USA during the war, and were retold and, no doubt, embellished, by barflies like Putzi Hanfstaengl, whose anecdotes provided much of the basis for Langer’s psychoanalytical account.

Sir Richard J. Evans: The Third Reich in History and Memory (Kindle Locations 2343-2346). Little, Brown Book Group. Kindle Edition.

Nor did the unveiling of Köhler’s “secret” derive from fresh archival evidence that would force academic historians to reconsider their dim view of such speculations about Hitler, based as they are largely on entertaining rumours that circulated around the bars of Europe and America. In place of evidence, Köhler based his history written as a farce on a speculative interpretation of just a single word (Untergang), passed off as incontestable certitude. Or as Joachim Fest noted in his review of Köhler’s book:

Köhler... writes “without doubt”, where considerable doubt has been raised, and “certainly” exactly where no certainty exists.

Köhler ... schreibt “zweifelsfrei”, wo erhebliche Zweifel angezeigt sind, und “sicher”, wo es gerade keine Sicherheit gibt.

Joachim Fest: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 1997. My translation.

In other words, the basic tenet of this literature is that the less the evidence, the greater the certainty—but best of all is when there is no evidence at all, since that would be the equivalent of smoking gun evidence conferring transcendental certitude.

Köhler’s grand conspiracy about Hitler’s secret “mission” to transform the world according to a Wagnerian Masterplan have predictably been ignored by academic historians, along with Köhler’s claims to having “unveiled” the operatic origins of World War II and the Holocaust. The hoax should have ended then with a healthy squall of laughter, since not a single academic historian accepts that Party ideology originated in nineteenth-century opera along with a conspiracy of silence to “veil” the “terrible” “origin [of National Socialism and the Final Solution] in the Wagnerian world”.

Unfortunately, there exists such a yawning gulf between academic historiography and pop history, that despite having recanted his views, Köhler’s sensationalist speculations have taken on a life of their own, as it does its rounds with the usual lot of wacky conspiracy theories on the internet. Köhler’s ideas form the basis of the layperson’s understanding of the origins of one of the major events in history—all conveyed in gross oversimplifications and distortions allowing the uneducated masses to run roughshod over every nuance found in academic tomes dedicated to the serious study of the era.

Parallels with Daniel Goldhagen’s Hitler’s Willing Executioners

Köhler’s conspiracy theories shared much in common with Daniel Goldhagen’s populist book, Hitler’s Willing Executioners, which, although unanimously condemned by virtually all historians across the world, has gripped the layperson’s imagination:

|

| The German edition of Daniel Goldhagen’s Hitler’s Willing Executioners translated into German as Hitlers willige Vollstrecker |

It is no coincidence that in German translation, the title of Goldhagen’s 1996 book shares the word “Vollstrecker” (executant) in common with Köhler’s 1997 book, which, in German, is Der Prophet und sein “Vollstrecker”. The basic tenet of Goldhagen’s book is that:

Genocide was immanent in the conversation of German society. It was immanent in its language and emotion. It was immanent in the structure of cognition.

Goldhagen: Hitler’s Willing Executioners, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1996, p. 449

It was predictable that someone would exaggerate Goldhagen’s thesis to claim that the influence of Wagnerian opera alone sufficed to brainwash “The German Mind”, programming it so as to make genocide “immanent in its language and emotion”, and “immanent in the structure of cognition”.

Along with arguably the greatest of all Holocaust scholars, Raul Hilberg, who said “I take exception to Goldhagen’s thesis, which is worthless” (quoted in Rosenbaum), Sir Richard J. Evans expressed dismay at Goldhagen’s vast pop appeal to a lay audience as his book hit the top of the bestseller list, writing that:

... the debate over [Goldhagen’s] book has opened up yet again the gulf between academic and popular history. The most popular general history of Nazi Germany is still William L. Shirer’s The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (1960), which takes a similar line to that of Goldhagen, and repeats wartime propaganda about the pervasiveness of antisemitism, racism, militarism and authoritarianism in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century German culture.

Sir Richard J. Evans: Rereading German History. My emphasis

|

| Professor Raul Hilberg, the author of a landmark three-volume study, The Destruction of the European Jews, called Goldberg’s book “worthless”. Widely regarded in his time as the world’s leading Holocaust scholar, Hilberg failed to mention Wagner once in the entire 1536 pages of this seminal work. The third and final edition of Hilberg’s study appeared years after the publication of Köhler’s book, but Hilberg disdainfully ignored Köhler’s ultra-Goldhagenist views as being equally “worthless”. Hilberg regards discussion of nineteenth-century opera as an utter irrelevance to the subject. Musicologists studying Wagner need to either follow Hilberg’s example or risk violently rewriting worldhistory from a grossly distorted opera-centric perspective. |

Like Joachim Köhler, William L. Shirer is another non-academic journalist who replaces nuanced analysis of complex historical phenomena with simplistic formulae fit for mass consumption fuelling the quick sale of books on a subject for which the public shows an insatiable appetite. Authors like Shirer who repeat anti-Hun war propaganda have long been left behind by academic historians, their views dismissed as a crude populism that cannot be considered serious academic historiography.

Evans went on to dismiss Goldhagen’s book (originally his PhD thesis) as a “startling failure of scholarship”, attributing it to him being a political scientist rather than a historian, thus lacking knowledge of the background historiographic literature:

How can we explain this startling failure of scholarship in a book which after all began its life as a Harvard dissertation? It is surely relevant to note that it was supervised and examined not by historians but by political scientists, whose knowledge of the empirical aspects of the subject was clearly limited. ... Not surprisingly, for all its resonance in the press, serious British specialists in German history, including Ian Kershaw and Arnold Paucker, condemned the book as ignorant and simplistic ...

Sir Richard J. Evans: Rereading German History. My emphasis

The principal aim of this critical review of Köhler is to confront this wave of “ignorant and simplistic” populism, which makes crude assertions flying in the face of serious academic historiography. There is a common link between Köhler, Shirer, and Goldhagen. All of these populist writers push an “ignorant and simplistic” caricature of “The German Mind”, as the singular sufficient cause of a German Sonderweg leading straight to Hitler. The controversial concept of the Sonderweg is often translated as “special path”. However, sonder can mean strange, weird, or peculiar in German. The word Sonderling means a “weirdo”, literally a “strangeling”. The Germans are caricatured as being the strangelings of European culture, and German culture caricatured as the quintessential expression of an innate and deep-seated genocidal streak inherent to “The German Mind”:

Goldhagen argues that Germans killed Jews in their millions because they enjoyed doing it, and they enjoyed doing it because their minds and emotions were eaten up by a murderous, all-consuming hatred of Jews that had been pervasive in German political culture for decades, even centuries past. Ultimately, says Goldhagen, it is this history of genocidal antisemitism that explains the German mass murder of Europe’s Jews, nothing else can.

Sir Richard J. Evans: Rereading German History. My emphasis.

Even in Germany, lay audiences supported Goldhagen with rapturous applause during public debates against leading left-wing historians like Hans Mommsen. Faced with this profoundly negative caricature of Kraut-hate, Köhler reacted with an explosive mixture of hate and self-hate, in which chaotic feelings of guilt, anger, and resentment drove him to seek redemptive expurgation through a convenient wholesale blame-shifting onto Wagner, who ended up the scapegoat chosen to bear the cross of his nation’s future sins, with Hitler as the Resurrection and Second Coming of history’s original operatic Ur-Kraut. The identities of Wagner and Hitler merged into one as WagnerHitler, and the histories of their timelines, 1813–1883 and 1889–1945 respectively, were likewise merged into a single homogeneous epoch stripped of the slightest discontinuity.

Köhler had thereby enthroned Wagner as The Lord of the Strangelings, and declared guilty of having single-handedly masterminded the course of German history down the path of its historical Sonderweg—straight to the crematoria of Auschwitz. Wagner’s works had been interpreted according to the a priori assumption as to the correctness of the Goldhagen interpretation of history, resulting in views of Wagner’s work infinitely more nazified than anything any National Socialist ever dreamt of, and, in a circular argument, such interpretations had then been proffered as evidence of the correctness of the Goldhagenist view of history. In this tautological paradigm, the orgiastic enjoyment of murdering Jews by the million was viewed as having been aestheticised by Wagner into a sublime expression so intense as to have decisively programmed “The German Mind” so that its very “structure of cognition” would make the rise of National Socialism a preordained historical inevitability.

The Failure of the Sonderweg Hypothesis

Ron Rosenbaum rightly points out that attempts to locate the origins of National Socialism and the Final Solution in German cultural and literary roots have a long history, and represent little more than tired old 1950s clichés:

... the effort to find the deep root, the ur-explanation of Hitler and the Holocaust in some intrinsic pathology of German culture was something German intellectuals themselves had been seeking for decades since the war. One version of what might be called “German exceptionalism” was the notion of the “Sonderweg”—the special path German history and culture had taken in the centuries since the Reformation. In its more pointed, more self-lacerating form, this became the postwar “Schuldfrage” controversy—the blame question, in which some German thinkers contended there was something not merely exceptional but deeply darkly wrong in German culture. That the violent extremism of thought to be found in Nietzsche and Wagner made Hitler possible if not inevitable.

Rosenbaum: Explaining Hitler: The Search for the Origins of His Evil (Chapter 19: Daniel Goldhagen: Blaming Germans)

Sir Ian Kershaw also tells us that this type of thinking had its roots in wartime anti-German propaganda when he wrote of:

...the crude interpretation of Anglo-American writers after the war, that Nazism could only be seen as the culmination of centuries of German cultural and political misdevelopment reaching back to Luther and beyond. [Footnote 12: Classics of the genre are Rohan O’Butler, The Roots of National Socialism (London, 1941), and William Montgomery McGovern, From Luther to Hitler. The History of Nazi–Fascist Philosophy (London, 1946). Such anti-German distortions were massively popularized in William Shirer’s bestseller, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (New York, 1960).]

Sir Ian Kershaw: The Nazi Dictatorship: Problems and Perspectives of Interpretation (Bloomsbury Revelations) (p. 9). Bloomsbury Publishing. Kindle Edition.

Both Köhler and Goldhagen had thus failed to say anything original at all, and merely represent shrill attempts to revive the archaic Sonderweg theory long rejected by mainstream historians specialising in this era, especially when Sir Richard J. Evans noted that:

In a curious way, this echoed the Nazis’ own version of German history, in which the Germans had also held by some kind of basic racial instinct to these fundamental traits [such as militarism, hatred of human rights and democracy], but had been alienated from them by foreign influences such as the French Revolution.

Evans: The Coming of the Third Reich: How the Nazis Destroyed Democracy and Seized Power in Germany

Nor would anyone still entertaining the old-fashioned “blame question” (Schuldfrage) permit all blame to be shifted wholesale and in its entirety onto a single nineteenth-century opera composer.

The protestations of Sir Richard Evans against such a monocausal culture-centric view of the Sonderweg have fallen on deaf ears outside of academic historical circles. Nor is Evans an isolated voice in the community of academic historians, for the overwhelming majority of historians ignore Köhler, and have about as much time for him as they have for Nazi UFO and Satanist conspiracies.

Yet outside of historiographic circles an ever-growing pop literature has been allowed to balloon, pushing ever more exaggerated views about Wagner’s allegedly all-dominant influence in shaping Party ideology—an “alternative” literature based on “alternative facts” entrapped in its own self-certain and secluded tautological bubble, oblivious to the degree to which such theories have been shunned by serious historians.

Admittedly, allusions to such pop literature can occasionally be found surprisingly even coming from professional historians. For example, historian Mike Rapport states in his book on the 1848 German Revolution:

It was still a long way from 1848 to 1933 but one disillusioned German ‘fourty-eighter’ who was a harbinger of that dark future was the composer Richard Wagner...

Rapport 1848: Year of Revolution, p144. Hachette Digital, London, 2008

However, Rapport is no specialist in the Dritte Reich era. He casually implies that, after participating in the 1849 pro-democracy uprisings musket and grenade in hand, Wagner’s disillusionment with violent revolution as a means of social change turned him into the “harbinger” of National Socialism. What sets Köhler apart is the way he would build an unstable construct of an operatic Sonderweg leading straight to National Socialism with Wagner as the demonic playwright who had scripted the course of world history a half-century after his death, based on the romantic fairytale about the course of history having been steered by “The Darker Side of Genius”. Such myths about musical talent having Satanic origins have a long history in music, with Niccolò Paganini having been refused a church burial due to rumours of his talents having been acquired from the devil, and it is said that Domenico Scarlatti would cross himself at the mention of Handel’s talents as an organist. The speculation that Wagner misused his musical talents to exert Satanic influence over world events after his death are just another variant of this myth which enjoys widespread currency in equally lurid Nazi Satanist literature where Wagner is regarded as an “intuitive” practitioner of “Tantric sex magick [sic]” (more on this subject later).

|

| Köhler presents a romanticised caricature of Wagner as a kind of Dr Evil using Tantric sex magick to manipulate his Mini-Me Hitler puppet from beyond the grave |

Exculpating Hitler

A key objection noted by Ron Rosenbaum is the unacceptable consequence of accepting Daniel Goldhagen’s theory of “eliminationist anti-Semitism”—such theories exculpate Hitler of guilt by displacing the weight of responsibility away from him:

... like all explanations that narrow their focus too sharply to a single point, the eliminationist anti-Semitism hypothesis inadvertently but implicitly tends to exculpate those factors it eliminates from primacy: Christian anti-Semitism, European cultural hostility to the Jews, the Nazi Party (which becomes in this view less the evil inciter and instigator of German hatred than the obedient servant of the evil wishes of an evilly conditioned German people). Even Hitler is, to an extent, exculpated. If Germany was pregnant with murder, that pregnancy was not his monstrous conception; he just brought the hot towels and boiling water to assist in its delivery.

Rosenbaum: Explaining Hitler: The Search for the Origins of His Evil (Chapter 19: Daniel Goldhagen: Blaming Germans)

Nazi opera conspiracies “narrow their focus” down so “sharply to a single point” that even Hitler and his Party were exculpated of the primacy of their guilt, as a nineteenth-century opera composer was scapegoated at the convenient exclusion of a vast plethora of complex socio-political factors eliminated from primacy. Hitler’s role had been reduced to that of a midwife delivering Wagner’s pre-formed “monstrous conception” with which he had left “The German Mind” pregnant. In his review of Köhler’s book, entitled Wagner’s Willing Executioner in a clear reference to Goldhagen’s Hitler’s Willing Executioners, Joachim Fest also remarked on this exculpation of Hitler:

[Köhler’s] thesis diminishes the primacy of Hitler’s criminality just as it blows Wagner’s choleric, often seemingly merely peevish, anti-Semitism out of all proportion until it attains the prominence of a cohesive ideology.

Joachim Fest: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 18th July 1997 (my translation)

If Hitler had been captured and placed on trial, any claim to innocence on the grounds of operatically induced insanity would have been heartily laughed out of court. The responsibility for the crimes of National Socialism lies not with a long-dead opera composer, but with Hitler and his fascist regime. To assert otherwise would be to exculpate Hitler and his Party.

A Craven Surrender to Nazi Propaganda

On vilifying Wagner as The Lord of the Strangelings and “harbinger” of the Holocaust, polemicists have glorified themselves as heroic Nazi hunters. Yet their actions involve a craven surrender to National Socialist propagandist attempts to reinvent their tub-thumping as an inspired movement rooted in great art. It legitimises propagandist attempts to hide behind a bowdlerised version of Wagner as a fig leaf to conceal the hollowness of its rhetoric. Rather than deflating the empty and bloated Führermythos, it merely helps to inflate that mythos to ever more exaggerated heights. It seems those who follow the Hitlerist path of studying the Dritte Reich as a phenomenon dictated by psychology and culture, are so held in thrall by that mythical facade that they stand paralysed before it, quivering in their boots, unable to see past the spectre.

For to lend their bloated beer-hall ideology an air of legitimacy, National Socialist propaganda alleged that artists like Leonardo da Vinci, Shakespeare, Dickens, Cervantes, Dante, Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, and Wagner had all represented visionary forerunners and “prophets”. They used this phoney narrative to crown themselves the supreme heirs to the Western cultural tradition as an artistically inspired movement, in order to elevate beer-hall ideology out of the gutter up to the zenith of Western civilisation.

This is why Sir Ian Kershaw tells us in his Hitler biography:

Kubizek’s later claim that Hitler had read an impressive list of classics—including Goethe, Schiller, Dante, Herder, Ibsen, Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche—has to be treated with a large pinch of salt. Whatever Hitler read during his Vienna years—and apart from a number of newspapers mentioned in Mein Kampf we cannot be sure what that was—it was probably far less elevated than the works of such literary luminaries.

Kershaw: Hitler—Hubris 1889–1936

As Sir Ian Kershaw tells us, Hitler’s background was far less elevated than high philosophy:

Hitler’s scene was less high-flying. His milieu was that of the beer-table philosophers and corner-cafe improvers of the world, the cranks and half-educated know-alls.

Kershaw: Hitler—Hubris 1889–1936

Timothy Ryback likewise reminds us that the cultural influences on Hitler of far greater impact were that of the petty bourgeois pop culture and kitsch-culture industry of his immediate historical milieu rather than major nineteenth-century Romantic era thinkers:

Hitler’s essential core ... was less a distillation of the philosophies of Schopenhauer or Nietzsche than a dime-store theory cobbled together from cheap, tendentious paperbacks and esoteric hardcovers, which provided the justification for a thin, calculating, bullying mendacity.

Timothy Ryback: Hitler’s Private Library, p175

The problem with locating the origin of National Socialist in the writings of great poets and philosophers of the past is that it ends up being an inflationary romanticisation of Nazi beer-hall propaganda, obsequiously surrendering to them the honour of hegemony over European culture. Post-Marxist thinker, Ernst Bloch’s demand to concede nothing to National Socialist claims to cultural legitimacy not only ends up forgotten but violently overridden:

The music of the Nazis is not the Prelude to Die Meistersinger, but rather the Horst-Wessel-Lied; they deserve credit for nothing else, and no more can or should be given to them.

From Über Wuzerln des Nazismus (1939). In the Suhrkamp Verlag edition of his works: Politische Messungen, Pestzeit, Vormärz, p.319-320.

Hitler’s ideology of beer-hall thugs simply does not deserve elevation out of the beer-hall to the lofty heights of Nietzsche and Wagner even for the convenience of polemic. Or as Sir Ian Kershaw puts it:

Hitler, the nonentity, the mediocrity, the failure, wanted to live like a Wagnerian hero. He wanted to become himself a new Wagner—the philosopher-king, the genius, the supreme artist. In Hitler’s mounting identity crisis following his rejection at the Academy of Arts, Wagner was for Hitler the artistic giant he had dreamed of becoming but knew he could never emulate, the incarnation of the triumph of aesthetics and the supremacy of art.

Kershaw: Hitler—Hubris 1889–1936

While many a Jewish mother may give her blessing to polemics against Wagner, and teach her children to hate him to commemorate the memory of victims of the Shoah and keep alive the flames of Kraut-hate, however well intentioned this may be, it is hard to see how turning the victims of National Socialism into extras in a giant opera production can honour victims in any way. Any distorted historiography of this era, however seductive it may be, does the memory of the victims of the regime no justice, especially where this involves a failure to demythologise and deromanticize National Socialism by academically stripping it down to the nakedness of its imminent historical contingencies.

The Nazi Opera Conspiracy Theory

Fails to Impress Historians

In his 1997 review of Köhler’s book, Joachim Fest notes that Köhler’s title seemed exaggerated: Hitler’s Wagner might have been more logical than Wagner’s Hitler. After all, Richard Wagner (1813 – 1883) died six years before Adolf Hitler (1889 – 1945) was born, making it more logical to write about how Hitler pushed his personal interpretation of Wagner for propaganda purposes. However, in the exaggeration essential to conspiracy theories, Hitler’s role in world history became little more than that of an opera impresario manipulated by a puppet-master. This is why Köhler’s book was entitled Wagner’s Hitler suggesting Wagner’s ownership of Hitler and his crimes.

The dead Wagner thus possessed Hitler to ghostwrite Mein Kampf leading Köhler to attribute quotes from Mein Kampf to Wagner before concluding that they were saying the same thing. Or to quote Sir Richard Evans’s review “phrases and quotations are time and again ripped from their context in the writings or sayings of Hitler and Wagner, and made to look as if they are saying the same thing”.

Joachim Fest was to remark on the astonishing diligence (“erstaunenswerten Fleiß”) of the author in researching his book. In a later essay published shortly before his death in 2000, Fest also calls Köhler’s book a “polemic”:

|

| Famous German historian and key Hitler biographer, Joachim Fest, contributed to a series of essays edited by the great Israeli Holocaust historian Saul Friedländer |

|

| Joachim Fest is scathing in dismissing Köhler’s “Polemik” (polemic) over "Wagner's Hitler". Fest in Richard Wagner im Dritten Reich, p 25 |

The Stark Contrast with Mainstream Academic History

To bring the reader back down to earth, I can only sincerely plead with readers to earnestly study the writings of genuine academic historians’ accounts of the Dritte Reich or Holocaust coming from recognised authorities on the era such as Sir Ian Kershaw, Sir Richard Evans, Saul Friedländer, Peter Longerich, Hans Mommsen, Christopher Browning, Raul Hilberg, Mark Roseman, Zara Steiner, David Cesarani, or John Toland. You will find that not one of such heavyweights amongst modern academic historians much bothers to mention Richard Wagner’s name (other than rarely en passant), let alone partitioning any blame to him, since no genuine historian permits reduction of WWII and the Holocaust to operatic history. A product of a lifetime of study, Raul Hilberg’s landmark three-volume study of the Holocaust does not make a single mention of any nineteenth-century opera composers, and credulous readers are invited to confirm this for themselves by conducting a Google search of every word in each volume by following the following links:

The Destruction of the European Jews: Volume I

The Destruction of the European Jews: Volume II

The Destruction of the European Jews: Volume III

Although Wikipedia is not always a reputable source of information, the entry on the Holocaust is exceptionally well-written, but neither the English language nor the Hebrew language versions once mention Wagner. As for the trolls to this blog who insist that rejecting Nazi opera conspiracy theories, as Raul Hilberg does, constitutes Holocaust denialism, they are at liberty to edit the Wikipedia entry so that it states this—along with an amendment to the biographic details on Raul Hilberg replacing the current statement hailing him as “the world’s preeminent scholar of the Holocaust” with one calling him a Holocaust denier. The Wikipedia editors will welcome your vandalism in much the same way as if you had edited the entry on the moon to say it was made of cheese.

However upsetting the petulantly self-righteous may regard this, it is an inescapable fact that you will no more find a reputable academic Holocaust historian state that a nineteenth-century opera composer caused the Holocaust than you will find a qualified astrogeologist asserting that the moon is made of cheese. Nor do historians any more debate whether the Holocaust was caused by a nineteenth-century opera composer than climatologists debate whether anthropogenic climate change really exists. The non-historian is duly invited to confirm this for themselves, and if this review encourages readers to do nothing else than to study seminal mainstream works on the history of the Dritte Reich and Holocaust, then this present review would have been worthwhile. Readers are also strongly encouraged to go to the Yad Vashem Institute website, which promotes education and quality academic research on the Shoah, with readers also being offered online educational courses.

Nor since the publication of Köhler’s book, has any respected historian come remotely near trashing decades of peer-reviewed academic research to replace it with Köhler’s comic book narrative where Hitler is seen as a puppet, forced by his Meister to enact an operatic Meisterbefehl for war and genocide. However deep the emotional Kraut-hate appeal such reductivistic narratives may retain, they represent dead-ends that prevent us from studying serious academic accounts of a seminal event in history from which we still have much to learn. For that reason alone it is imperative that we refuse to allow grossly oversimplified and distorted narratives to overshadow serious academic historiography.

Thus, while Köhler’s book asserted with a well-nigh transcendental level of incontestable certitude that Hitler worked according to a premeditated operatic Masterplan, most historians today strongly doubt the existence of any preformed Masterplan whatsoever:

For the stepwise fulfillment of the escalation of exclusion of Jews from German society up to the “Final Solution” after 1933, the increasing consolidation of hatred towards the Jews represents a conditional, but not sufficient factor. Likewise, the Holocaust never in itself sprang out of a consistent “Masterplan”.

Hans Mommsen: Das NS-Regime und die Auslöschung des Judentums in Europa. My translation (the Anglicism, “Masterplan”, in the original German text has been retained, and has not been corrected to “Master Plan”).

Köhler’s thesis, however, strongly overrode this position by concluding in one foul sweep that there not only was a Masterplan, but that it took the form of a grand operatic Meisterbefehl to occultly “transform the world into a Wagnerian drama”. It could have hardly been more fantastically out of step with the state of the current scholarly literature on the origins of the Final Solution.

Likewise, in the minor footnotes to his landmark Hitler biography to which Köhler is banished, Sir Ian Kershaw expressed full agreement with his illustrious colleagues, Sir Richard J. Evans and Joachim Fest:

It is nevertheless a gross oversimplification and distortion to reduce the Third Reich to the outcome of Hitler’s alleged mission to fulfil Wagner’s vision, as does Köhler, in Wagners Hitler.

Kershaw: Endnote 121 from Hitler: 1889-1936—Hubris

Köhler’s, Wagners Hitler, takes this [reduction of history to opera] on to a new plane, however, with his overdrawn claim that Hitler came to see it as his life’s work to fulfil Wagner’s visions and put his ideas into practice.

Kershaw: Endnote 129 from Hitler: 1889-1936—Hubris

Joachim Fest also expressed grave concern about the lack of academic neutrality and replacement of all nuance with a dubious polemic reminiscent of a “petulant prosecution”:

With an astonishing diligence he has brought sometimes disparate sources together as it supports his viewpoint, but basically what he presents is less an investigation than a petulant prosecution [ein gereiztes Plädoyer]. ... The dubious accusatory character of the book renders any nuanced differentiation an impossibility. According to Köhler everything ideological is already prefigured in Wagner: the hatred of the Jews, the eternal exterminationist rage, and the system of elaborate justifications. Only the question of “how”—“of its technical feasibility”—as he calls it, did he yet leave open a vacancy that Hitler reputedly filled. What he saw as his historic mission, was nothing more than the actualisation of Wagnerian postulates and Hitler consequently merely the political executioner thereof.

Joachim Fest: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. My translation and emphasis

Similar views expressing concern about the gross exaggeration of the alleged influence of nineteenth-century opera on Hitler have been expressed by leading Israeli historians such as Na’ama Sheffi:

Wagner is accepted [in Israel] with such difficulty because he is being manipulated as the symbol of National Socialism and the memory of the Holocaust. Therefore his anti-Semitic comments and their influence on the National Socialist regime, however ill defined, have been very much exaggerated.

Na’ama Sheffi: Interview with Die Welt. My translation and emphasis.

Notice that Sheffi states that Wagner is being manipulated into the symbol of the Holocaust. That is why you get these people who think that, far more than Hitler, Wagner is the face of the Holocaust. That is why they state that anyone who rejects Nazi opera conspiracy theories is a Holocaust denier, even if that means accusing all Holocaust historians of Holocaust denialism. But in legal terms, there is no such thing as symbolic guilt of a crime. To emotionally manipulate an ignorant mob into hating someone for their symbolic guilt of a crime committed long after they died is to make a scapegoat of them.

In Holocaust scholarship, such propagandist distortions of history fabricated to launch vengeful Kraut-hate attacks lacking academic neutrality have always been frowned upon. Nazi opera conspiracy theories are a way of surreptitiously indulging in such hate by wilfully manipulating Wagner into the Ur-Kraut and Ur-Nazi of world history suggesting that Wagner is incontrovertible evidence that “proto-Nazism” was all-pervasive in German culture well before the twentieth century. Similar polemics against other German historical figures including Luther, Hegel, Nietzsche, and Herder have largely lost popularity, leaving Wagner as the final bastion against whom such base populist hatreds are directed:

It has been all too easy for historians to look back at the course of German history from the vantage-point of 1933 and interpret almost anything that happened in it as contributing to the rise and triumph of Nazism. This has led to all kinds of distortions, with some historians picking choice quotations from German thinkers such as Herder, the late eighteenth-century apostle of nationalism, or Martin Luther, the sixteenth-century founder of Protestantism, to illustrate what they argue are ingrained German traits of contempt for other nationalities and blind obedience to authority within their own borders. Yet when we look more closely at the work of thinkers such as these, we discover that Herder preached tolerance and sympathy for other nationalities, while Luther famously insisted on the right of the individual conscience to rebel against spiritual and intellectual authority.

Yet there could hardly be a worse candidate against whom to direct such polemics—far worse so than Herder or Luther—since no major artist of comparative status in the entire canon of Western art fought so valiantly behind the barricades as a true patriot to his country in order to realise his artistic vision of democratic socialism. Unfortunately, for some pop historians, keeping alive the Kraut-hate sentiments of Allied war propaganda is so critical as to justify overwriting world history with a fictional narrative wielded as an instrument of belligerence for keeping the eternal flame of Kraut-hate alive. As a result, even some well-meaning individuals have fallen prey to the trap of accepting the opportunistic view of right-wing revisionist historians who have attacked German liberal thought emerging out of the 1848 pro-democracy revolution (including Wagner, Feuerbach, Marx and Engels) as being the very source of the Kraut-Think that historically predestined the rise and triumph of National “Socialism”.

Unlike the lay public, however, professional historians left such emotive anti-Hun narratives based on Allied war propaganda behind in the 1960s. As a result, the disconnection between populist Nazi opera conspiracy theories and mainstream historiography has become total. Nazi opera conspiracy theories exist in an alternative universe oblivious to the research of mainstream academic historians, who regard such conspiracies as they do similarly off-the-planet Nazi UFO conspiracies. Not even Daniel Goldhagen has come out to support Köhler, because he would not wish the collective exculpation of “The Germans” by narrowing of the focus of blame to just a single opera composer, forced to bear the cross of the sins of his future nation.

Another key reason Köhler’s theories are ignored by mainstream historians is that they amount to a claim that rather than being a product of cataclysmic socio-political disruptions—WWI, 1918-19 German Revolution, the Treaty of Versailles, hyperinflation, and the Great Depression—Hitler can be explained solely as a byproduct of romantic art and culture alone. Köhler’s book was subtitled in its English version, “a sceptical view”, since it claims to have discovered the real origins of WWII and the Holocaust in nineteenth-century romanticism alone, with a deep scepticism of academic historiographic emphasis on imminent socio-political and economic contextual determinants. It would certainly be a scandal were such a “sceptical view” of mainstream academic historiography accepted, since it would have necessitated at least as massive a rewriting of our current understanding of history as the acceptance of Holocaust denialism. Libraries full of studies would have had to be trashed to make room for the academic mainstreaming of Nazi opera conspiracies.

How Wagner is Forced to Fit Reductivistic Intentionalist Paradigms

Theories about the origins of the Final Solution can be broadly divided into paradigms that are intentionalist or structuralist (also called functionalist). Intentionalist paradigms claim that there existed a Masterplan forming a “straight path” towards the fulfilment of a well-defined premeditated plan to commit genocide on a vast scale, predating Hitler’s rise to power. Structuralist (or functionalist) paradigms locate the origins of the Final Solutions in a functional by-product of the unique socio-political power structure of National Socialist Germany amid the context of a catastrophic war of attrition. The structuralist paradigm posits a tortuous “twisted road to Auschwitz” in place of the simplistic “straight path” posited by intentionalists. Or as Steven R. Welch phrases it:

There was no straight path from Hitler’s anti-Semitic intentions to Auschwitz but rather a ‘twisted road’ characterised by haphazard development, improvisation and ad hoc decisions by various groups within a chaotic polycratic system of rule. The Final Solution arose in a piecemeal fashion, emerging through responses by local Nazi officials to the immediate context created by the war.

Steven R. Welch: A Survey of Interpretive Paradigms in Holocaust Studies and a Comment on the Dimensions of the Holocaust (download from Yale University website)

|

| Most modern scholars accept the idea of a “twisted road to Auschwitz” |

Here, by way of contrast, is a good summary of the intentionalist paradigm written by Elly Dlin (former director of the Dallas Holocaust Museum):

Gerald Fleming (among others) makes reference to documents, speeches, utterances and testimonies about Adolf Hitler (including ones that predate his joining the National Socialist Party in 1920) to trace an “unbroken continuity of specific utterances...a straight path...a single, unbroken, and fatal continuum...to the liquidation orders that Hitler personally issued during the war” (Gerald Fleming: Hitler and the Final Solution; p.13 and 24).

My emphasis

Dlin went on to say that:

The intentionalist school was fed by the solid tradition of fervent anti-Hun propaganda that emerged from both of the two World Wars in the 20th century Europe...

Hence why extreme intentionalist paradigms fabricate interpretations of Wagner’s opera as epitomising “Hun” thinking that typifies the allegedly ubiquitous “antisemitism, racism, militarism and authoritarianism in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century German culture” (Evans) of the sort that made genocide inevitable. Allied anti-Hun propaganda also formed the mirror image of National Socialist propaganda alleging the national character, which ran through the “pure” blooded German, had for all time been violently anti-Semitic and fanatically militaristic in its chauvinistic nationalism, with Wagner being forcibly interpreted as the archetypal case in point that proved this prejudice beyond doubt.

Once extreme intentionalism is accepted, it becomes logical that Wagner has to be made out to have steered German history down an “unbroken continuity of specific utterances...a straight path...a single, unbroken, and fatal continuum...to the liquidation orders that Hitler personally issued during the war” following the script of an operatic Masterplan of grand premeditated intentions handed directly from Wagner to Hitler. Interestingly, these sorts of anti-Kraut propagandist interpretations of Wagner as history’s original Hun appeared only with the outbreak of world war, suggesting that such interpretations are themselves by-products of historical circumstance.

These wartime propagandist readings of Wagner stand in marked contrast to the sort of interpretation presented by the likes of George Bernard Shaw in his pre-war 1898 book, The Perfect Wagnerite, emphasising the Feuerbachian socialist revolutionary aspects of The Ring. Shaw’s book highlights how the wartime politicisation of Wagner interpretation has engendered a gross reductivism, lowered to the level of crude propagandist slogans.

|

| Shaw’s book, The Perfect Wagnerite, revealed the revolutionary socialist side of Wagner. The full text of the book even features on the Marxist.org website. |

Furthermore, there exists a spectrum of ideas as to the origin of the Final Solution, ranging from extreme intentionalist paradigms to extreme structuralist paradigms, along with those more moderate theories which are intermediary, or even forming a synthesis of both:

Extreme Intentionalism

Moderate Intentionalism

Moderate Structuralism (Functionalism)

Extreme Structuralism

Synthetic

Most modern historians fall into the synthetic to moderate structuralist camp. At the far extreme intentionalist end of the ideological spectrum lies Daniel Goldhagen who posited the origins of the Holocaust in a purely culturally predetermined and fanatically exterminationist anti-Semitism allegedly so imminent to the structure of cognition of “The German Mind” as to have made it predestined that someone like Hitler would make “willing executioners” of all Germans—once again curiously matching the same view pushed by National Socialist propaganda.

Sir Richard J. Evans thus says of Goldhagen that “his book constitutes a craven surrender to the Nazi view of German history” (Rereading German History) in that it entailed a wholesale acceptance of the propagandist line that Hitler was little more than the humble servant of the Will of the German People (der Wille des deutschen Volkes) to fulfil their unique Destiny of eliminating the Jews—a transcendental Will allegedly present for centuries in all Nordic-Germanic Aryan people, as expressed in the writings of Luther, Wagner, and Shakespeare.

Nazi opera conspiracy theories occupy a unique position, one so extreme as to be off the standard scale in constituting the most grossly exaggerated form of hyperintentionalism, locating the origins of the Final Solution in toto out of a single word (Untergang) taken out of an essay from the writings of Richard Wagner, whose intentions Hitler and his Party allegedly carried out for the sole purpose of “transforming the world into a Wagnerian drama”. In the history of Holocaust scholarship, this constituted a uniquely hyperbolic reductivistic paradigm which locates the origin of the Final Solution to a microscopic point of historical ideological origin in just a single word written by a nineteenth-century opera composer. It posited an “unbroken continuity of specific utterances...a straight path...a single, unbroken, and fatal continuum” drawn from this microscopic focal point of origin of a single word, directly to the crematoria of Auschwitz.

This presents a position that radically precludes all possibility of structural influences from the “political and social realities of the time” in favour of a dogmatic paradigm dominated by the grossly monocausal intentionalist influence of nineteenth-century opera alone and in its entirety. It is a position so radically extreme that serious academics writing on the subject simply ignore this theory outright for being too comically exaggerated to even bother discussing. Not even those in the synthetic camp with a moderate intentionalist orientation such as Saul Friedländer, Yehuda Bauer (Professor of Holocaust Studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem), and Zara Steiner would ever support such an extreme position. However, its seductive simplicity, radically stripped of every nuanced convolution along a “twisted road” to Auschwitz, guarantees the raging popularity of Köhler’s extreme thesis with the lay public, thus suggesting that academic historians ought to critically tackle the explosive expansion of this populist opera conspiracy literature in the same way that the profession systematically debunked Holocaust denialism.

When most serious historians doubt whether there was even a clearly defined and premeditated “intentionalist” programme to commit genocide right from the start, it naturally seems rather ludicrous to suggest that the single-minded political mission of the National Socialists can be reduced with such perfect certitude to nothing other than that of a secret intentionalist programme to obediently execute the “vision” of an almost hundred-year-old operatic Masterplan on the world’s stage—a “vision” whose existence is based entirely on the strained interpretation of just a single word (Untergang) taken out of context from an essay by a nineteenth-century opera composer for which no evidence exists of any leading Party member ever having read. Even as late as 1940 Heinrich Himmler wrote:

I hope completely to erase the concept of Jews through the possibility of a great emigration of all Jews to a colony in Africa or elsewhere. . . . However cruel and tragic each individual case may be, this method is still the mildest and best, if one rejects the Bolshevik method of physical extermination of a people out of inner conviction as unGerman and impossible.

Quoted from Christopher Browning’s book The Origin of the Final Solution p.70 of eBook edition.

In this same section of Himmler’s report can be seen Adolf Hitler’s personal hand-written comment: “very good and correct”.

It constitutes a far-fetched speculation to suggest that Himmler and Hitler had an abrupt change of heart, gripped with a violent desire to “transform the world into a Wagnerian drama”, resulting in the premeditated enactment of a Masterplan for an operatic Final Solution kept so secret by the Nazis that not a single historian has ever uncovered evidence for its existence. The unanimous conclusion of historians who have ignored Köhler is that if he really fancied himself as an Indiana Jones exposing sensational Nazi opera conspiracies, he should have stuck to writing fiction instead of pulp fiction disguised as history.

Most historians think that the organisational structure of the Party plus the catastrophic series of defeats against the Red Army brought about a set of “structural” circumstances that were unique in precipitating a so-called “cumulative radicalisation” colluding to engender the Holocaust. Historian Robert Gerwarth summarises this concept well:

Nazi Germany was not a smoothly hierarchical dictatorship, but rather a “polycratic jungle” of competing party and state agencies over which Hitler presided erratically. The “cumulative radicalisation” in certain policy areas emerged as a result of tensions and conflicts between powerful individuals and interest groups who sought to please their Führer by anticipating his orders. Within this complex power structure, individuals contributed to Nazi policies of persecution and murder for a whole range of reasons, from ideological commitment and hyper-nationalism to careerism, greed, sadism, weakness or—more realistically—a combination of more than one of these elements.

Robert Gerwarth: Hitler’s Hangman—the Life of Heydrich

However, Gerwarth’s acceptance that “hyper-nationalism ... careerism, greed, sadism, weakness or—more realistically—a combination of more than one of these elements” also accelerated the process of “cumulative radicalisation” demonstrates the fact that most modern historians are willing to combine elements of intentionalist paradigms into the framework of structuralist thinking.

On the other hand, historians will inevitably disregard Nazi opera conspiracy theories, since this posits a grossly oversimplified theory based on the sweeping assumption that far from being a messy “polycratic jungle”, National Socialist Germany was a harmoniously organised teleological structure neatly centred around its single-minded devotion to secretly “transform the world into a Wagnerian drama”.

The Alien Abduction Methodology of Nazi UFO Conspiracy Theories

The way Köhler took his “gross oversimplification and distortion” onto “a new plane” has been perhaps rather harshly been described to read like an alien abduction account—an accurate metaphor, however, as far as the grossly speculative methodology goes. After all, Köhler’s methods compare well to that of similar kitschy and sensationalist pseudo-histories on the Dritte Reich. For example, there is an extensive Occult Reich literature with luridly sensationalised accounts of Nazi Satanism, as well as allegations of cover-ups of Nazi survivalism, or, worse still, risible pseudo-histories involving Holocaust denialism. There is even a story about WWII being caused by Hitler’s missing testicle, or by Hitler going mad from neurosyphilis contracted from sex with a Jewish rentboy. Another equally bizarre story claims that UFOs are secret Nazi weapons developed in conjunction with the aliens to be used for their impending world-domination:

|

| Joachim Köhler belongs firmly in a long tradition of sensationalist pseudo-histories about National Socialist Germany. Köhler’s Nazi opera conspiracy is close kin to Nazi UFO conspiracies |

Fantasies, urban legends, literary inventions and pure lies came after the war at the beginning of the ‘60s. Any book that dealt with Nazis and the occult, Satan, UFOs or secret treasures was assured to be sold at thousands of copies. Among the purely commercial approach of fake historians and storytellers, there were a few “honest” though fanatic people who managed, by their writings and teachings, to develop a kind a semi-religious version of Nazism that has formed the basis up until today for neo-Nazi movements throughout the world.

Frank Lost: Nazi Secrets. My emphasis

Yet beneath such populist sensationalism often creeps an insidious right-wing revisionist historicism that dismisses the influence of socio-political and economic structural realities that condition history in favour of a romantic culture-centric view of history following a script written by dead poets and philosophers. It is a view that avidly feeds a “semi-religious” mythical view of a romanticised National Socialism that forms the basis of neo-Nazi movements today. Köhler represents a kindred romanticisation since he stated explicitly that the “political and social realities of the time” along with the “interests of the nation whose Chancellor he was” were totally irrelevant to understanding what drove Hitler, since the sole sufficient cause for the “special path” history took was nineteenth-century romantic art.

Once the imminent socio-political contextual background is deleted from our understanding of Hitler and replaced with that of late nineteenth century romantic opera, this account becomes ahistorical. That is why historians refuse to accept the view that National Socialism can be seen as a Dead Poets’ Society operated under remote control from beyond the grave by long-dead literati or thinkers such as Richard Wagner or Martin Luther. Figures such as Wagner and Luther belong to a different era, born of different socio-political contexts which they were addressing with their ideas. So disparate are such historical contexts that no a priori assumption of transcendental teleological continuity between them and that of twentieth-century fascism can be made.

If the National Socialists did romanticise history by implying that they stood on the shoulders of many a Great Man, this was pure self-adulatory propaganda, one that aimed to manufacture a phoney glow of cultural legitimacy and of a mythical historical “Destiny”, but which does nothing to change their original radicality born of their violent severance from the past, as engendered by that most radical of all discontinuities from the past—namely the catastrophic socio-political disruption of World War I and its social aftermaths.

Texts such as Mein Kampf or the Second Book (Zweites Buch) are thus pervaded with a fanatical engagement with the living “political and social realities of the time” such as World War I, the humiliation imposed on Germany by the treaty of Versailles, the rise of Marxism after the Russian revolution, the Freikorps, the German Revolution of 1918-19, the struggle for imperialist expansionism into new Lebensraum, and the coming conflict with the Soviet Union and America. Attempts to wring readings out of Hitler’s writing to the effect he ignores the political context of his age in favour of an escape into a fantasy world of nineteenth-century opera are speculatory to the point of being totally off-the-planet.

It is fanciful nonsense to suggest that Hitler was a twentieth century King Ludwig who had gone mad from excessive preoccupation with Wagnerian opera, causing him to neglect his stately duties in the “interests of the nation whose Chancellor he was”, in its place striving to “transform the world into a Wagnerian drama”. Wagner simply is not the playwright who scripted the course of world history, for no one person can have so much influence on the world, least of all a dead one. Even Hitler’s importance in shaping the Dritte Reich is arguably much exaggerated over broader socio-political structural determinants.

Rather than Wagner being transcendental proof that history runs under remote control according to the thoughts of dead poets and philosophers, he is, on the contrary, proof that art is powerless to steer the course of history. Wagner’s pacifist and anti-capitalist vision in The Ring of apocalyptic annihilation for the Gods of War that rule the world no more ended Bismarckian militarism than the Weimar era cabaret singers satirising Hitler in gay and lesbian clubs brought down the Dritte Reich. Art is sufficiently open to interpretation that it can easily be manipulated by demagogues to support ideologies diametrically opposite to those of the artist. Instead of listening to the artist, especially when someone like Wagner left a vast legacy of letters and prose works, most people listen to the demagogue instead.

It is purely wishful thinking of the sort that belongs in a romantic fairy world to imagine that twentieth-century history would have turned out differently if only German history had not been hijacked down the path of a Sonderweg by Wagner’s “dark genius”. It may be heartbreaking to many, but as much as those in the arts may crave to believe otherwise, the toad that must be swallowed is that art simply does not have such magico-romantic power over society or the course of history. Nor is having an interest in opera sufficient justification for a reader of history to collapse world history down to operatic history.

... time and again Wagner called for the annihilation of the Jewish race, an alien body in an Aryan German state. Hitler took him at his word.

Presumably, these “aliens” Taylor references were of the ufological, Close Encounter kind, since a meticulous search of his complete writings and letters demonstrates that never once did Wagner come close to calling for such a thing, and Taylor failed to provide a bibliographic citation in Wagner for us to verify the statement: it does not exist. Nor did Köhler ever “time and again” show us examples where Wagner ever stated such a thing. As Sir Richard Evans notes, Köhler kept quoting Hitler and then attributing the quote to Wagner—time and time again. Wagner himself is never allowed to speak for himself for more than a few words before Köhler jumps in to lecture us about what the quote “really” means—enter the quotation from Mein Kampf, placed straight in Wagner’s mouth. The one time Wagner is allowed to speak for more than one sentence, it turns out that Köhler has tampered with the quote.

To read Köhler is like reading a well-documented account of an alien abduction. The supermarket shopping docket shows he was in that area at a particular time and place, likewise the receipt from the petrol station, then the dent on the car and the little bruise to the forehead is shown etc etc ad nauseam. Then, after endless, yet excruciatingly detailed—but ultimately banal—documentation, the punch line hits: “then the aliens abducted me—I have proven it”. All the astonishing diligence in meticulously collecting documentation—the detailed dockets, the endless pictures of the little dent on the side of the car—it all supposedly proves “the aliens abducted me”. You then scratch your head and wonder how on earth the fantastic leap to the unsupported conclusion appeared out of left field.