Hitler’s Philosophers by Yvonne Sherratt

Published May 01, 2013 by Yale University Press

Softcover version:

ISBN-10: 0300205473

ISBN-13: 978-0300205473

Hardcover version:

ISBN-10: 0300151934

ISBN-13: 978-0300151930

The edition used for this review: Kindle eBook version ASIN: B00B3R1E0O

In many ways, Hitler’s Philosophers by Yvonne Sherratt had the potential to be an interesting subject of serious academic research. Instead, the reader is fed unadulterated pulp fiction in the guise of history—and aggressive neo-Thatcherite revisionist rewriting of history—one which scarcely befits its description as a serious academic study. Heavily reliant on the acceptance of Daniel Goldhagen’s Hitler’s Willing Executioners, a book described by the doyen of Holocaust historians, Raul Hilberg, as “worthless”, much the same could be same of Sherratt’s own Goldhagenist scribblings. Sherratt even condescends to crudely derogatory sexism in her polemic against Hannah Arendt by constantly referring to Arendt as “Hannah” (male authors are never referred to by their first names) along with a pathetic “docudrama” in which this tough-minded, chain-smoking twentieth-century intellectual heavyweight is reduced down to an “eighteen-year-old girl” (sic).

Even more unfortunately, this is the second such book from Yale Press I have critiqued within a short period of time, and the third overall, each taking the form of a thinly veiled ultra right-wing polemic accusing the left of “Nazism”—an enormous shame given that Yale Press also publish Raul Hilberg’s landmark three-volume historiographic study of the Holocaust: The Destruction of the European Jews. Obviously, Sherratt’s book escaped peer review by a professional historian with even the slightest of expertise in the field. Together with Joachim Köhler’s Wagner’s Hitler—The Prophet and his Disciple, Sherratt’s book represents a prime example on how to pass an extreme right-wing revisionist polemic off as an academic historiography of the period.

In some ways, everything that is worth saying about Sherratt’s book has already been more than adequately said by Sir Richard J. Evans in his justly damning review of her book for the Time Higher Education, in which he concluded with the words:

There are interesting and important things to be said about the relationship between philosophy and Nazism, that most anti-intellectual of political creeds, but you will not find them here.

Evans: Times Higher Education (my emphasis)I can only implore readers to study Evans’s superb review—and extremely carefully so, simply because there is an astonishing amount of quality information jam-packed into its short space. The reader learns vastly more from the review by Evans than from the entirety of Sherratt’s ridiculous book. On the other hand, the cynical pre-emptive ad hominem attack on all prospective critics by Yale Press should be universally condemned:

Sherratt not only confronts the past; she also tracks down chilling evidence of continuing Nazi sympathy in Western Universities today.The meaning of this dictate is simple: either be forced to accept Sherratt’s views or be forever condemned as a Nazi. In other words, Sherratt is uncriticizable, reflecting similar assertions from Daniel Goldhagen, who, in the face of overwhelming criticism from historians from Cambridge to Tel Aviv to Vermont, could counter only by proclaiming his assertions to be “incontestable”. Sherratt is right now probably gloating over the fact that the very existence of criticism of her book is “incontestable” evidence of such “continuing Nazi sympathy” today.

Readers unfamiliar with the work of Cambridge historian, Sir Richard J. Evans, need only know that he was the key expert witness taken on for the David Irving vs. Deborah Lipstadt case. The incisive expert testimony of Evans was instrumental in the systematic demolition of the notorious Holocaust denier, David Irving’s, reputation. Evans went on to write a book about the David Irving trial:

So when Professor Evans writes a devastating review of Sherratt’s book that is as uncompromisingly damning of her right-wing revisionist pseudo-history as of the lies from David Irving, it pays to sit up and give due attention to its every single written word. Any attempt to dismiss the highly critical review by Professor Evans as being an example of such “chilling evidence of continuing Nazi sympathy in Western Universities today” could not possibly be wider of the mark.

My only real regret about the review of Hitler’s Philosophers by Professor Evans is that it is way too short and pithy. I fear that many readers may miss the remarkably pointed cogency of the ideas that are packed into his review. So even though, in some ways, the review says everything anyone could have wanted to about Sherratt’s piece of pulp fiction in the guise of history, in other ways I just wished it could have been longer and more comprehensive. The shortness is likely due to an editorially enforced word limit, although it could just as easily have been a case of Evans contemptuously dispatching Sherratt with short shrift. Perhaps Professor Evans simply felt the book unworthy of his time or effort in getting the rightful full-blown demolition it deserves. Fortunately, Evans peppers his review with fleeting allusions to subjects he has published about in more detail elsewhere. This allows us to reconstruct what the full-length version of his review might have said. Such a reconstruction is precisely the aim of this present review.

|

| Dr Yvonne Sherratt |

Sherratt is a lecturer at Bristol University, where her current profile at the time of writing states that:

Yvonne Sherratt has an Undergraduate, Masters and Doctoral degree from Cambridge University. She studied at Newnham College, Cambridge before becoming a postgraduate at King’s College, Cambridge and then went on to win a prize research fellowship at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, which she held for three years. She has taught at a number of universities including Cambridge and New College, Oxford before coming to Bristol.

Yvonne Sherratt currently teaches two Masters programmes, ‘Researching Society and Space’ and ‘Geographies of Knowledge: Nazi and Jewish Academics’.Yvonne Sherratt’s teaching areas of expertise include:Philosophy of Social ScienceEuropean—French and German hermeneutics, critical theory, genealogy, phenomenology, deconstructionism, postmodernism. Analytic—Kuhn, relativism, sociology of science.Social TheoryMarx, Weber, Durkheim, Parsons, etc. Gender, Frankfurt School, Foucault, Psychoanalysis. Freud and psychoanalysis, Structuralism, Post-structuralism, Functionalism, Deconstructionism. Critical Theory.Political TheoryPlato, Aristotle, Machiavelli, Montesquieu, Rousseau, J. S. Mill, Kant, Hegel, German Romanticism, Nietzsche, Kierkegaard, Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre, Marx, Marxism, Post-Marxism, Habermas, Hannah Arendt, Gadamer. Feminist theory from Mary Wollstonecraft. Concepts - Authority, the State, Justice, Sovereignty, Rights, Power, Materialism, Idealism, Democracy etc.Cultural TheoryTheories of urbanism, space, social change, Walter Benjamin, Frankfurt School, Adorno, Foucault, early and late work, Heidegger, Sartre, existentialism, Edmund Husserl, Feminism, Simone de Beauvoir, Albert Camus, French post-structuralism, Derrida, Deleuze, Lacan, Paul Ricoeur, Clifford Geertz. Nature and Romanticism, Aesthetics, Plato, Aristotle, Kant, Burke, Hegel, Nietzsche etc.

From Bristol University professional profile as of July, 2014Unfortunately, all of this astonishes me. That someone alleging to be an “academic” should so shamelessly condescend to write a trashy piece of pulp fiction in the guise of history like this utterly beggars belief. Even the author admits as much. As Evans points out in his review:

The problems start with the author’s confession that this is not an academic work but a “docudrama…which aims to transport the reader to the vivid and dangerous world of 1930s Germany” [Sherratt, p.2]. There is indeed a lot of scene-setting, much of it not really necessary...

Evans: Times Higher EducationThe histrionic “docudrama” (sic) style seems to have been adopted so as to allow Sherratt to pass her fairy tales off as serious historiographic research. Frighteningly, Sherratt even seems to be using the book as the basis of a Master’s course at an ‘academic’ faculty. Another reviewer for Marx and Philosophy also noted that:

The main problem with Sherratt’s text is its narrative style. I feel that her attempts to take the reader through unnecessarily descriptive explanations often detract from her research, I found myself repeatedly checking her notes to see whether she was taking artistic license in the delivery of the material.

Sean Christopher Goda for Marx and PhilosophyI could not agree more: what is the point of replacing matter-of-fact academic styled presentations with meandering fairy tales (“docudrama”) unsupported by citations—other than to pull the wool over the readers’ eyes? A typical example of a particularly histrionic use of this docudrama style is this:

Sherratt even indulges in rampant speculation over details of the execution by guillotine of Kurt Huber:Now terrified, she ran to get past them to warn her father; the men blocked her way but she ducked beneath them, blistering her nails on the balustrade and screamed, ‘Poppi, Poppi, the police are here’.

The caretaker cursed—warm, wet weather made his job even more irksome. The executions were scheduled for 5 p.m. and he had been tired, sweating profusely, looking forward to his day’s work coming to an end, when news had arrived that several SS officers wanted to observe the last execution. This would cause a delay. Spitting, he thought, how bloody minded can these officers be? Didn’t they realise that would add over an hour to his work day? —No extra pay, of course. And more to the point, things would have to be properly cleaned before they came. He had bent double over the guillotine, making sure he had removed all traces of blood; hair had got caught up and knotted in the blade, which made it harder to polish? Disinfectant was in short supply, so he had had to remove the dirt and human grime physically, scrubbing hard to remove the stains. If he didn’t get the job done properly, the officers would complain and there’d be yet more work. But nobody had thought about him [1].Only on looking up the details of footnote [1] hidden away at the end of the book does the reader discover the author confessing that “the details of the caretaker are my own reconstruction”. Reconstruction based on what? Sherratt fails to reveal her sources. Sadly, it appears that the reader is left with little choice but to conclude the “reconstruction” is based entirely on artistic licence—namely upon pure fantasy.

At other times Sherratt simply has her facts completely incorrect. For example:

Adorno enjoyed the company of other members of the Schönberg circle too [no supportive citation].

Sherratt, Yvonne: Hitler's Philosophers (p. 180). Yale University Press. Kindle Edition.Far from it, Arnold Schoenberg actually took an intense disliking to Theodor Adorno:

I have never been able to bear the fellow [i.e. Adorno] ... it is disgusting the way how he treats Stravinsky. I am certainly no admirer of Stravinsky, although I like a piece of his here and there very much—but one should not write like that.

Of Julius Friedrich Lehmann, Sherratt states that he was “a racist scientist [sic] and a publisher” (p. 19). However, Lehmann was merely a publisher who had no formal medical or scientific qualifications whatsoever. It is nonsense to credit Lehmann with the accolade of being recognised as a “scientist”. A more credible study of “intellectual” influences on Hitler by Timothy Ryback tells us:

...the remnant Hitler library contains a cache of books that is almost certainly more central to the shaping of the dark core of Hitler’s worldview than the high-minded musings of Schopenhauer, Fichte, and Nietzsche: more than fifty volumes inscribed to Hitler between 1919 and 1935 by Julius Friedrich Lehmann, an individual who has the dubious double claim to being both the single most generous contributor to Hitler’s private book collection and the public architect for the Nazi pseudoscience of biological racism.Ryback, Timothy W.: Hitler's Private Library: The Books that Shaped his Life (Kindle Locations 2015-2019). Random House. Kindle Edition.

It is typical that the author most heavily represented in Hitler’s private library scarcely rates little more than a fleeting mention in Sherratt’s book.

[Hitler] was at this time a mere provincial politician, but with extremist fantasies [no supportive citation]. He loved fire [no supportive citation]. He enjoyed the power of its destruction, its vivid light, rank smoke and ability to destroy in seconds that which took centuries to form [no supportive citation]. He was an impatient man with a passion for the immediate, the dramatic [no supportive citation].

Sherratt, Yvonne: Hitler's Philosophers (p. 3). Chapter 1: Hitler: The Bartender of Genius. Yale University Press. Kindle Edition. My emphasis.Later Sherratt alleges that Hitler’s request to have his body burnt in petrol after his suicide represented the ultimate consummation of a “pyromaniac fantasy” rather than representing a desire to avoid having his body publically displayed for passing crowds to spit and urinate on as had already happened to Mussolini and his mistress:

Shortly afterwards, ‘two corpses were taken and placed side by side ... and petrol ... was poured over them’. A rag was dipped in petrol and set alight and flung upon the corpses. They were at once enveloped in a sheet of flame. Hitler’s last pyromaniac fantasy had been indulged.

Sherratt, Yvonne: Hitler's Philosophers (p. 230). Yale University Press. Kindle Edition.Sherratt gives us no citation to check regarding her claims that “Hitler loved fire”, so I looked up several key biographies of Hitler by Alan Bullock, Sir Ian Kershaw (Volumes One and Two), Joachim Fest, John Toland, and Volker Ullrich, as well as the four-volume Third Reich series by Sir Richard J. Evans. I could find nothing whatsoever to corroborate Sherratt’s speculations. None of these major sources ever once comes remotely near corroborating Sherratt’s claims.

Though this represents a radical deviation from mainstream historiographic accounts of Hitler, not a single aspect of Sherratt’s “diagnosis” of pyromania is supported with anything remotely resembling a bibliographic citation or a cogent psychological study based on a systematic psychiatric mental state examination of credible evidence—astonishing, considering this is a text to be used for a Master’s teaching programme. This would have required a whole chapter, if not a book, but the closest thing to evidence Sherratt can provide is a claim to being “meticulously researched”. Sadly, Sherratt demonstrates a woeful lack of awareness that strict diagnostic criteria must be fulfilled in order to correctly diagnose pyromania:

A. Deliberate and purposeful fire setting on more than one occasion.

B. Tension or affective arousal before the act.

C. Fascination with, interest in, curiosity about, or attraction to fire and its situational contexts (e.g., paraphernalia, uses, consequences).

D. Pleasure, gratification, or relief when setting fires, or when witnessing or participating in their aftermath.

E. The fire setting is not done for monetary gain, as an expression of sociopolitical ideology, to conceal criminal activity, to express anger or vengeance, to improve one’s living circumstances, in response to a delusion or a hallucination, or as a result of impaired judgment (e.g., in Dementia, Mental Retardation, Substance Intoxication).

F. The fire setting is not better accounted for by Conduct Disorder, a Manic Episode, or Antisocial Personality Disorder.

From DSM-5 American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.Not a shred of evidence is presented that Hitler fulfilled these diagnostic criteria.

There is naturally no compulsion to slavishly adhere to the DSM-5 or the ICD-10-CM diagnostic criteria, but it if Sherratt has utilised her own modified diagnostic criteria, based upon her own vast clinical experience, it is critical that this be explained and justified. In the absence of such clear-sighted academic clinical analysis, Sherratt presents us instead with rampantly speculative psychobabble speculating that Hitler was some pyromaniac bartender, thus instantly putting Sherratt’s book in the same basket as those suggesting he went berserk because of his allegedly missing testicle or from tertiary neurosyphilis contracted through sex with a Jewish rentboy.

In the old days, before the systematic elimination of reductionistic Freudian explanations, pyromania used to carry strongly psychosexual connotations, which have been mercifully expurgated from the modern DSM and ICD diagnostic criteria. Particularly since Sherratt’s Bristol University profile reveals an interest in Freudian and Lacanian psychoanalysis, the speculative diagnosis of pyromania probably reflects Sherratt’s unfortunate attempt at reviving a psychosexually based reductionistic Hitlerism:

The ‘Hitlerism’ argument will not go away. In fact, there are some signs, amid the current preoccupation with sexuality in history (as in everything else), that the old psycho-historical interpretations are making a comeback, and in equally reductionist fashion. Hence, we have recent attempts to reduce the disaster of nazism to Hitler’s alleged homosexuality, or supposed syphilis. In each case, one or two bits of dubious hearsay evidence are surrounded by much inference, speculation and guesswork to come up with a case for world history shaped fatefully and decisively by Hitler’s ‘dark secret’.

Sir Ian Kershaw in Hitler, the Germans and the Final Solution. My emphasisYou can see the very same formula at work in Sherratt’s book, with ideas constructed around one or two bits of dubious evidence surrounded by “much inference, speculation and guesswork” culminating in the supposed revelation of Hitler’s ‘dark secret’, as Sherratt proclaims that:

... the academy held a terrible secret: the story of how philosophy was implicated in genocide.

Sherratt, Yvonne: Hitler's Philosophers (p. 2). Yale University Press. Kindle Edition. My emphasisThe quote about Hitler being “a bartender of genius” turns out to have been culled uncritically from the exceedingly problematic source of Hanfstaengl, and presented to the reader as though it were an indubitable fact. However, the reliance on the questionable sources of Strasser, Hanfstaengl and Rauschning is typical of this grossly speculative psycho-historical literature:

The other group that has joined the Freudians in promoting the notion of a sexual secret—indeed, formed, in effect, a strange explanatory alliance with them—consists of a number of embittered ex-Nazi defectors from Hitler’s inner circle, former intimates such as Otto Strasser, Ernst Hanfstaengl, and (to a lesser extent) Hermann Rauschning. If the mostly Jewish Freudians lacked inside information and the former Nazi insiders lacked objectivity and theory, the two groups found—at a distance—common ground in their vision of Hitler, with the Freudians frequently adapting the Strasser and Hanfstaengl perversion stories as confirmation for their speculations.

Ron Rosenbaum: Explaining Hitler: The Search for the Origins of His Evil (chapter 8)Concerning Ernst “Putzi” Hanfstaengl, whose colourful anecdotes Sherratt enthusiastically accepts as holy writ, Sir Richard J. Evans tells us:

Hitler suffered from ‘schizophrenic mania’ according to a later German attempt to analyse his personality; or, in an even less plausible scenario, he never woke up from the hypnosis to which he was allegedly subjected following the ... hysterical blindness he suffered after ... a gas attack.... Neither of these two theories is supported by any evidence. The problem with many of such speculations is that the evidence they use is unprovable except on the basis of the kind of rumours that circulated round the bars of Europe and the USA during the war, and were retold and, no doubt, embellished, by barflies like Putzi Hanfstaengl, whose anecdotes provided much of the basis for Langer’s psychoanalytical account.

Evans: The Third Reich in History and Memory. Chapter 9: Was Hitler Ill? My emphasisThis uncritical reliance on a dated speculative psychohistorical literature, which has largely been discredited as being little more than salacious psychobabble, casts immense doubts on Sherratt’s claims about her book that:

It is a work of non-fiction, carefully researched, based upon archival material, letters, photographs, paintings, verbal reports and descriptions, which have all been meticulously referenced.

Sherratt, Yvonne. Hitler's Philosophers (p. 2). Yale University Press. Kindle Edition. My emphasisIt is exceedingly peculiar for any academic text to start off with an introduction proclaiming itself to be “carefully researched” and “meticulously referenced”, while reassuring the reading that the “docudrama” contained therein actually is “non-fiction”. If Sherratt’s book were indeed graced with such supreme virtues, as Sherratt feels free to attribute to herself, she would likely have felt no need to blow her own trumpet over the stupendous qualities of her research, as such qualities would speak for themselves. Moreover, Sherratt would have actually critically scrutinised the reliability of sources such as Hanfstaengl, and refused to have passed rampant speculation off as fact. Sherratt even condescends to using the totally discredited source of Hermann Rauschning with only an extremely scant attempt at justification:

The quotes I use from Rauschning are consistent in their representation of the Führer’s character with other accounts such as those of Martin Bormann endorsed by Trevor-Roper.

Sherratt, Yvonne. Hitler's Philosophers, endnote 31. Yale University Press. Kindle Edition.Since right-wing historian, Trevor-Roper’s time (who merrily authenticated the egregiously fake Hitler Diaries), Rauschning has entirely fallen into disrepute. Thus Kershaw says that:

I have on no single occasion cited Hermann Rauschning’s Hitler Speaks, a work now regarded to have so little authenticity that it is best to disregard it altogether.

Sir Ian Kershaw: Hitler 1889-1936: HubrisSir Richard J. Evans talks about:

...dubious and discredited sources such as Rauschning’s Hitler Speaks, a record of interviews most of which never took place outside Rauschning’s mind.

The dubious reliance on speculation fuelled by the occasional morsel of information from problematic sources totally undermines the credibility of Sherratt’s claim that her book is “meticulously referenced”. When you consider that there have been similarly speculative claims about Hitler’s alleged perversity stemming from him being gay, having a missing testicle, signing a compact with Satan, or having gone mad from tertiary syphilis caught off a young Jewish rentboy, piling more speculative rubbish upon rubbish like this is utterly unhelpful to us gaining genuinely insightful understanding of this seminal historical figure. This sort of wildly speculative “docudrama” involving satanism, UFOs, latent homosexuality, or missing testicles is immensely popular with the general public, but it merely gets in the way of genuine academic historiography.

An example of Sherratt’s dubious methodology is when she makes up the claim that:

Kant, Hegel and Nietzsche were as sacred to the German people as Shakespeare and Dickens were to the British... Respect for the great men of the past must once more be hammered into the minds of our youth: it must be their sacred heritage. Hitler’s fervent desire to be the most authentic of all Germans made these iconic figures [no supportive citation] deeply alluring.

Sherratt, Yvonne. Hitler's Philosophers (p. 16). Yale University Press. Kindle Edition.But the National Socialists did regard Shakespeare and Dickens as sacred Nordic-Protestant and völkisch-Germanic artists. Sherratt alleges that the National Socialists equally revered all famous German philosophers based on little more than being a famous German. That turns out to be a false assumption by Sherratt arising from her core dictum that ’em Krauts are all the same. However, Sherratt forgets that socialist thinkers Feuerbach, Marx, and Engels also belong to the great heritage of German thought, yet the National Socialists hardly considered them “sacred”.

Although Sherratt claims that Hegel held a revered place in the canon of National Socialist icons, she fails to provide any evidence for this. Hitler only ever once mentioned Hegel on record, only to repeat Schopenhauer’s polemical dismissal of Hegel as an “insipid, mindless, revoltingly nauseating, ignorant charlatan” (ein platter, geistloser, ekelhaft-widerlicher, unwissender Scharlatan) (Schopenhauer: Fragment on the History of Philosophy), a “repulsive, mindless charlatan, an unparalleled scribbler of nonsense” (Schopenhauer: Chapter VI, Book II, World as Will), and to quote Shakespeare”s Cymbeline in English calling Hegel’s writings “such stuff as madmen tongue and brain not” (Schopenhauer: Über den Willen in der Natur). In his diaries, Hermann Goebbels states in an entry dated the 13th of May, 1943 that Hitler merely reiterated Schopenhauer’s arrant contempt for Hegel:

Likewise, party propagandist, Alfred Rosenberg, only ever expressed abject contempt for Hegel, possibly due to Hegel’s inherent Spinozism, and definitely due to his profound influence on Feuerbach, Marx, Engels and Lenin. Concerning the great Jewish philosopher, Spinoza, Hegel declared:Hegel is a thoroughly slavish philosophical bondsman of the princes. He deserves, in the opinion of the Führer, the harsh and ruthless intellectual pillorying which he undergoes from Schopenhauer.Hegel ist ein durchaus gebundener philosophischer Fürstendiener; er verdient, wie der Führer meint, die harte und rücksichtslose geistige Stäupung, die er von Schopenhauer erfährt.Aus den Tagebüchern von Joseph Goebbels seine Unterredungen mit Adolf Hitler. From the Diaries of Joseph Goebbels, His Conversations with Adolf Hitler 1939/1945: Volume 2, January 1943 - March 1945 (German Edition) (Kindle Locations 3215-3216). Sketec - Publishing House, Passau. Kindle Edition. My translation.

Spinoza is the high point of modern philosophy: either you are a Spinozist or not a philosopher at all

Geschichte der Philosophy III, p163, Suhrkamp Verlag.

Spinoza ist Hauptpunkt der modernen Philosophie: entweder Spinozismus oder keine Philosophie.

|

| “Either you are a Spinozist or you are not a philosopher at all” Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel |

Rosenberg made it absolutely clear that he regarded Hegel as Marx’s predecessor:

After the collapse of absolute monarchy in 1789, Democratic principles struggled with the National idea. Separated from the start, and later bringing both movements into rigidity, a new doctrine of power alien to the blood was formulated which reached its peak in Hegel. It was then taken over in renewed falsification by Karl Marx, who equated state with class rule.

Rosenberg: The Myth of the Twentieth Century: An Evaluation of the Spiritual-Intellectual Confrontations of Our Age, p.346It is possible that Alfred Rosenberg might have been aware of the fact that Lenin had famously said:

It is impossible completely to understand Marx’s Capital, and especially its first chapter, without having thoroughly studied and understood the whole of Hegel’s Logic. Consequently, half a century later none of the Marxists understood Marx!

Vladimir I. Lenin: Conspectus of Hegel’s Science of Logic (1914)Rosenberg further talked about:

Abstract popular sovereignty of Democracy and the contemptuous words of Hegel... have produced the same insubstantial scheme of so called state authority.

Rosenberg: The Myth of the Twentieth Century: An Evaluation of the Spiritual-Intellectual Confrontations of Our Age, p.347. My emphasis.And again:

Logic is the science of God, said Hegel. These words are an affront to a truly Nordic religion. It is the antithesis of all that is truly German and all that was truly Greek. These words are truly Socratic. It is not surprising therefore that university professors have canonised Hegel along with Socrates.

Rosenberg, Alfred: The Myth of the Twentieth Century: An Evaluation of the Spiritual-Intellectual Confrontations of Our Age (p. 193). Kindle Edition.

Despite the fact that the National Socialists clearly hated Hegel as an “insipid, mindless, revoltingly nauseating” proto-Marxist whose words are “such stuff as madmen tongue and brain not”, Sherratt declares that:

Hegel’s influence on Hitler has been noted by other scholars [in the plural]: ‘it is possible to detect Hegel’s view of the State having “supreme power over the individual” in Hitler’s writings and speeches’ [singular citation to Frank McDonough’s Hitler and the Rise of the Nazi Party].

Sherratt, Yvonne. Hitler's Philosophers (p. 22). Yale University Press. Kindle Edition.What McDonough writes is this:

While in Landsberg fortress, Hitler claimed he read works by Nietzsche, Hegel, Houston Stewart Chamberlain and Treitschke, even though those present at the time later claimed he rarely read such works in any detail.

The omission of McDonough’s final qualifying line represents grossly unprofessional distortion and misrepresentation of secondary sources in a situation that required credible primary source material to support it in the first place. For Hitler might have claimed to have been extraordinarily well read, but that was pure self-adulatory narcissism. It is certainly true that Hegel’s polemicists have alleged to have “discovered” proto-Nazi ideology in Hegel in much the same way that President Obama’s political enemies claim that his political thought is just a garbled rehash of Mein Kampf. Yet neither McDonough nor Sherratt are able to give us primary source citations of Hegel ever stating that the State has “supreme power over the individual”, at least not any more than they have a credible proof demonstrating that Obama takes his inspiration from Mein Kampf. That is because Hegel never said any such thing about the state having “supreme power over the individual”.McDonough, Frank: Hitler and the Rise of the Nazi Party (Seminar Studies) (p. 55). Taylor and Francis. Kindle Edition. My bold emphasis.

|

| Sherratt’s crudely polemical caricatures of Hegel-Hitler are about as convincing as this depiction of Obama-Hitler found on the internet |

Nor did Hitler ever preach, as Sherratt claims he does, that:

Copying Hegel, Hitler preached of a force within history: ‘Just think: over a period of some two thousand years we can follow the German people in history, and never in the course of history has this people possessed this single formation both in the conceptions of its thought and in its action...’ [citation to a Hitler speech]. From German Idealism, Hitler stole the notion of a single idea animating world history. ‘The miracle is that [there] arose this mighty unity in Germany, this victory of a Movement, of an idea …’ [citation to a Hitler speech].

Sherratt fails to provide credible evidence to support her claim that Hitler was an authority on Hegel who read him well, “copied” Hegel, quoted from him, and was deeply influenced by him.Sherratt, Yvonne: Hitler's Philosophers (p. 33). Yale University Press. Kindle Edition.

Nor does Sherratt make clear where this phrase “a force within history” comes from since no such phrase occurs in Hegel’s writings—nor does Sherratt, in her supposedly “meticulously referenced” book, have the simple academic decency to provide a reference that could be checked. So I was forced to undertake detailed electronic word searches of several major digitalised texts by Hegel (The Phenomenology of Spirit, The Philosophy of Right, Lectures on the History of Philosophy, and all three parts of the complete Encyclopaedia including The Science of Logic). Nothing was found in these texts, so a search was undertaken of the Werke: Vollständige Ausgabe (complete works) of Hegel in digital format, which uncovered search 353 hits to the word “historisch” (historical). The word “Geschichte” (history) hit the current maximum 500 hit limit, but none of these 500 hits undercovered the alleged quote, so the words combinations of “in der Geschichte”, “in Geschichte”, and “innere Geschichte” were used instead. Searches around German synonyms of the word “force” (Kraft, Macht, Zwang, Gewalt, Wucht, Stärke) were also undertaken. Only one hit including a word like “force”, namely “Naturmächte” (powers of nature) used in a passage together with the “history” (Geschichte) was uncovered:

In this view, it is only the powers of nature which in truth act in history, and men and gods, though they belong to heaven, and are chosen for the summit of Olympus, are forfeited to nature and profoundly immersed in the very root of the earth, to be ruled unconditionally and blindly by its necessity.In dieser Ansicht seien es nur Naturmächte, die in Wahrheit die Geschichte wirken, und Menschen und Götter, obgleich diese dem Himmel angehören und auf dem Gipfel des Olympus ihren Sitz gewählt, seien doch in innerster Wurzel gleich erdenhaft und an die Natur verfallen und von ihrer Notwendigkeit unbedingt und blind beherrscht.Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich. Werke: Vollständige Ausgabe (German Edition) (Kindle Locations 98558-98561). Talpa. Kindle Edition. My translation.

The reader can see that it bears no resemblance to Sherratt’s Hitler quote. This exhaustive fact-checking exercise only further shows that Sherratt thought she would get away with asserting the existence of Hegelian influences, imagined whenever Sherratt encounters Hitler using commonplace words such as “history” and “ideas”, under the assumption that nobody would spend hours checking her claims against the texts of Hegel’s complete works. For example, Sherratt goes on:

From German Idealism, Hitler stole the notion of a single idea animating world history [no supportive citation]. ‘The miracle is that [there] arose this mighty unity in Germany, this victory of a Movement, of an idea...’ [citation to a Hitler speech]

Sherratt, Yvonne: Hitler's Philosophers (p. 33). Yale University Press. Kindle Edition.The simple occurrence of the word “idea” in a political speech by either Hitler—or any other politician—hardly proves the influence of philosophy, idealist or otherwise. Only in the most vulgar reading of German Idealism would it be construed as being about “ideas” or a “single idea animating world history”. So once again I found myself forced to conduct an exhaustive search through the whole Hegel Complete Works in German. The nearest I could find to anything like “the notion of a single idea animating world history” was this quote:

The Spirit is invigorating [belebendes] law in union with the manifold, which is then animated [belebtes]. If a person posits this animated [belebte] manifoldness as a simultaneous multitude of many, and yet in conjunction with the invigorating [mit dem Belebenden], these individual organs, the endless whole, become an infinite universe of life...

Der Geist ist belebendes Gesetz in Vereinigung mit dem Mannigfaltigen, das alsdann ein belebtes ist. Wenn der Mensch diese belebte Mannigfaltigkeit als eine Menge von vielen zugleich setzt und doch in Verbindung mit dem Belebenden, so werden diese Einzelleben Organe, das unendliche Ganze ein unendliches All des Lebens...Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich: Werke: Vollständige Ausgabe (German Edition) (Kindle Locations 6768-6773). Talpa. Kindle Edition.

Once again, in this passage about the relation of the world-as-a-whole to its constituent parts (the relation of the Many to the One), contains nothing remotely resembling “the notion of a single idea animating world history” in it at all.

Thus Sherratt has failed miserably to substantiate the claim that National Socialist ideology was influenced by German philosophical Idealism in any way. Nor does Sherratt even give us an example of Hitler or any idealist philosopher ever using the bizarre phrase “single idea animating world history”, despite the fact that it is proclaimed to have been a key doctrine of both Hegel and the National Socialist Party a hundred years after Hegel’s death. Sherratt sadly evinces little evidence in her book that she has any more of an idea what romantic era philosophical Idealism actually entails than beer-hall expert, Hitler.

The exasperated Evans comes to the same conclusion that Sherratt’s book is thoroughly permeated with ridiculous unsupported speculations passed off as fact:

Unsupported assertions permeate the book. We are told that Hitler considered himself a “philosopher-leader”, and that his self-presentation as a prophet was directly derived from Nietzsche; no evidence is presented for either of these surprising claims.

Evans: Times Higher Education. My emphasisThe passage in Sherratt’s book alleging that Hitler saw himself as a “philosopher-leader” carries a bibliographic reference to the landmark biography of Hitler by Sir Ian Kershaw:

[Hitler] had to incorporate the subject of philosophy within his sphere [no supportive citation] and he soon adopted the fantasy that he himself was a great thinker [no supportive citation]. Indeed he would soon come to regard himself as the ‘philosopher leader’ [citation to Sir Ian Kershaw’s biography of Hitler: Hubris, 1998, p.250].

Sherratt, Yvonne: Hitler's Philosophers (p. 16). Yale University Press. Kindle Edition.My emphasisSherratt gives the misleading impression that Hitler himself had stated that he came to regard himself to as “the philosopher-king”. However, on looking up the original text, we find that Kershaw says absolutely nothing of the like. Not only does Sherratt’s statement lack a credible primary source citation to back up her “surprising” assertions, but she grossly misrepresents secondary sources as well. When you check Sherratt’s supportive citation, this is what Kershaw actually wrote:

Hitler, the nonentity, the mediocrity, the failure, wanted to live like a Wagnerian hero. He wanted to become himself a new Wagner—the philosopher-king, the genius, the supreme artist. In Hitler’s mounting identity crisis following his rejection at the Academy of Arts, Wagner was for Hitler the artistic giant he had dreamed of becoming but knew he could never emulate, the incarnation of the triumph of aesthetics and the supremacy of art.

Kershaw: Hitler—Hubris 1889–1936

It must first be said that any first-year philosophy undergraduate will know that the idea of the “philosopher-king” comes not from German philosophy, but from Greek philosophy—namely, Plato’s Republic. Whereas Kershaw writes “philosopher-king”, in the original Platonic sense, Sherratt not only shamelessly misquotes Kershaw by writing “philosopher leader”, but fails to declare the fact that these words represent Kershaw’s personal interpretation of Hitler, ripped completely out of context, rather than being a primary quote from Hitler directly announcing himself as “the philosopher leader” as Sherratt misleadingly implies. Notwithstanding the fact that Wagner is an opera composer rather than a philosopher, nowhere does Kershaw ever state that Hitler actually considered himself to be some sort of comical operatic philosopher-king. Nor does Sherratt even attempt to give a primary bibliographic citation to a credible primary source where either Hitler or a leading Party member can be found referring to their leader as “the operatic philosopher-Führer”.

This does nothing to stop Sherratt from considering her research so extraordinarily “meticulous referenced” that she can now go on to write repeatedly about Hitler as the operatic “philosopher Führer” as though her unsupported speculation were now an absolute and incontestable fact:

This does nothing to stop Sherratt from considering her research so extraordinarily “meticulous referenced” that she can now go on to write repeatedly about Hitler as the operatic “philosopher Führer” as though her unsupported speculation were now an absolute and incontestable fact:

Hitler took for granted the status of philosophy, and his egotism about the subject spread to a fantasy that he himself was a great thinker. Indeed he came to regard himself as the ‘philosopher Führer’. To this end he wrote Mein Kampf, in which he outlined his atrocious beliefs.

Sherratt, Yvonne: Hitler's Philosophers (p. 2). Yale University Press. Kindle Edition. My emphasisOnce again:

When Hitler came to power as chancellor in 1933 he had convinced himself and his Party that he was the ‘philosopher leader’. He had found ammunition from the past to bolster his fantasy, but now he needed to convert the world.

Sherratt, Yvonne: Hitler's Philosophers (p. 63). Yale University Press. Kindle Edition. My emphasisAnd yet again:

From 1933 and for the remainder of the decade Hitler’s dream was realized. By transforming himself into the ‘philosopher’ Führer, convincing the country of his genius, and sifting the past for its poisonous strands of thought, Hitler had paved the way for a new reality to underpin his world order.

Sherratt, Yvonne: Hitler's Philosophers (p. 127). Yale University Press. Kindle Edition. My emphasisAnd still yet again:

As his defeat became inevitable, and his generals started to question his leadership, Hitler began to panic [no supportive citation]. In his bunker in Berlin, this great ‘philosopher-leader’ who had seemed infallible raged like a madman

[no supportive citation].

Sherratt, Yvonne: Hitler's Philosophers (p. 229). Yale University Press. Kindle Edition. My emphasisAnd elsewhere Sherratt alleges she has uniquely penetrating insight into the inner working of Hitler’s imagination:

Hitler had set himself up as the ‘philosopher leader’—but only in his own imagination [no supportive citation]. He had yet to convince anyone else.

Sherratt, Yvonne: Hitler's Philosophers (p. 35). Yale University Press. Kindle Edition. My emphasisIf it cannot be firmly established by evidence that Hitler had unequivocally convinced himself that he was “the philosopher Führer”, as Sherratt alleges to have done through reading the mind of the dead, then the core tenet supporting the central thesis of the whole book just collapses. Sherratt fails miserably in her attempt to secure the credibility of her book’s central tenet, instead presenting the aggressive brute repetition of the same unsupported inference embellished with an audaciously self-certain tone imputing its incontestable certitude, as “proof”.

Elsewhere Kershaw provides us with more illuminating insights in his landmark Hitler biography, of a sort that contrast markedly with those of Sherratt:

Hitler’s scene was less high-flying. His milieu was that of the beer-table philosophers and corner-cafe improvers of the world, the cranks and half-educated know-alls.

Kershaw: Hitler—Hubris 1889–1936That is a far more accurate view of Hitler: the know-all, half-educated, beer-table “philosopher” and crank pseudo-intellectual. While Hitler would have delighted in being elevated from “beer-table philosopher” to the legitimate heir to the great German tradition of high philosophy, Sherratt gives us little reason to pander to his vanity as she obsequiously delights in doing.

Kershaw also reminds the reader that Kubizek’s claim about Hitler having read a whole host of high literary and philosophical luminaries is almost certainly propagandist nonsense:

Kubizek’s later claim that Hitler had read an impressive list of classics—including Goethe, Schiller, Dante, Herder, Ibsen, Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche—has to be treated with a large pinch of salt. Whatever Hitler read during his Vienna years—and apart from a number of newspapers mentioned in Mein Kampf we cannot be sure what that was—it was probably far less elevated than the works of such literary luminaries.

Kershaw: Hitler—Hubris 1889–1936

Sherratt fails to keep in mind the fact that Kubizek’s book, in which he makes these claims, started as a commission from the Party as a piece of National Socialist propaganda. It is propaganda that Sherratt eagerly laps up.

Unfortunately, historians have to put up with an enormous and ever-growing populist literature passing off every manner of lurid speculation about Hitler—a populist literature in which belligerently repeating wild speculation often enough turns falsehoods into incontestable “Truths”. Usually, historians cringe and ignore such literature outright, so Sherratt should consider herself privileged to receive constructive feedback from as imminent a historian as Evans—a remarkable review containing more useful insights than the whole of Sherratt’s book. If genuine historiographic research is to be presented for review by historians specialising in what is one of the most intensively studied eras of all time, it has to show awareness of the current literature, as well as being backed up with proper academic styled citations to credible sources—otherwise, the book goes in the bin along with Nazi UFO and missing testicle speculations. Unfortunately for Sherratt, the way Evans treats her unsupported speculations with dismissive disdain suggests that Sherratt might as well have presented historians with a “docudrama” about how Hitler was transported up to a UFO made by the Nazis in cooperation with the aliens, where his body is being kept in suspended animation ready to be reactivated for the impending Nazi UFO invasion of the world:

Unfortunately, Sherratt gives us little reason to suppose that her book has an iota more academic credibility than such a Nazi UFO “docudrama”.

One of the fatal weaknesses that Evans exposes is the fact that Sherratt shows a gross lack of awareness of current historiographic developments in the vast published literature on the Dritte Reich era. What she presents as original research turns out to be little more than a rehash of the sort of thing that used to be repeated around bars during the 1940s. Even after the war, the anti-Hun sentiment whipped up by war propaganda lead many English language speaking authors to demonise just about any German figure of history as being history’s original proto-Nazi Kraut, fit to be dutifully hated by patriots all and sundry. Unsurprisingly, if you read pre-WWI British literature on German philosophers, you will find none of these propagandist anti-Hun sentiments expressed anywhere. Sherratt seeks to revive this post-war pseudo-historiography based on wartime anti-German propaganda. In fact, Sherratt really need not have troubled us with a whole book, when really she needed only to have written one sentence: ‘em bloody Krauts—they’re all Nazis, always ’ave been, always will be.

|

| Sherratt’s book is based on Allied war propaganda: “those bloody Krauts are all the same” |

To quote Evans:

Back in the 1940s and 1950s, scholars such as Rohan Butler, William McGovern, Edmond Vermeil and Peter Viereck used to blame Germany’s philosophers for the rise and triumph of Nazism. Ripping quotation after quotation out of its contemporary context, they purported to show that Nazism’s core ideas had been held in advance by the entire German philosophical tradition, from Novalis to Nietzsche.

Evans: Times Higher Education (my emphasis)

Evans calls this a “teleological approach” to history. It is a view in which every sausage made in all of German history is seen as being some sort of quintessential link in the seamless continuum of a teleological chain pointing towards the providential rise and triumph of National Socialism in the twentieth century. It is a view that sees the seeds of National Socialism in anything German prior to the Dritte Reich era. Yet Sherratt provides no justification for viewing history in this dated manner, and just assumes that such a methodology can be accepted a priori without the slightest bit of critical thought. The biggest problem is that this teleological view tends to be highly self-serving in what it selects out as a prime example of proto-Nazism:

It has been all too easy for historians to look back at the course of German history from the vantage-point of 1933 and interpret almost anything that happened in it as contributing to the rise and triumph of Nazism. This has led to all kinds of distortions, with some historians picking choice quotations from German thinkers such as Herder, the late eighteenth-century apostle of nationalism, or Martin Luther, the sixteenth-century founder of Protestantism, to illustrate what they argue are ingrained German traits of contempt for other nationalities and blind obedience to authority within their own borders. Yet when we look more closely at the work of thinkers such as these, we discover that Herder preached tolerance and sympathy for other nationalities, while Luther famously insisted on the right of the individual conscience to rebel against spiritual and intellectual authority.

It is particularly noticeable that Christian right-wing authors like Peter Viereck hurriedly skip over the seminal religious figure of Martin Luther to instead shift the blame towards keys figures in the German liberal-humanist tradition of thought. Nazism, we are then told, is a form of Godless National “Socialism”. Likewise, Sherratt avoids mentioning Martin Luther’s name even once. Instead, the political left—including Feuerbach, Marx, Engels, Wagner, and Bakunin—is forced to shoulder the burden of blame for the rise of National “Socialism”.

|

| Marx and Engels regarded Feuerbach as a socialist thinker intermediary between Hegel and themselves |

The result is that, rather than National Socialist beer-hall pseudo-intellectualism being seen as a violent counter-reaction against the German liberal tradition of thought, it comes to be conveniently framed by right-wing historical revisionists as being the very teleological pinnacle of the German liberal academic tradition. National Socialism is thus framed as the apotheosis of “socialism”. Phrase after phrase is conveniently ripped out of context to “prove” the validity of such revisionist history. It is to this right-wing revisionist history that Sherratt chooses to lend her full weight of support as she insinuates that the Final Solution had Marxist origins:

Feuerbach’s anti-Semitic ideas were overshadowed by the notorious prejudice of Karl Marx. In On the Jewish Question Marx wrote:

Once society has succeeded in abolishing the empirical essence of Judaism—huckstering and its preconditions—the Jew will have become impossible, because his consciousness no longer has an object, because the subjective basis of Judaism, practical need, has been humanized, and because the conflict between man’s individual-sensuous existence and his species-existence has been abolished. The social emancipation of the Jew is the emancipation of society from Judaism.

Sherratt, Yvonne. Hitler's Philosophers (p. 43). Yale University Press. Kindle Edition.

Here Sherratt conflates different forms of anti-Semitism, implying it is all the same, and all of the same historical origin as National “Socialist” racial eliminationism. Sherratt not only overlooks the existence of religious Christian anti-Semitism, but conveniently omits all mention of the fact that Marx himself came from a Jewish background. Left-wing anti-Semitism like that found in a Marx or Feuerbach is something of an entirely different social origin and character to right-wing racially deterministic anti-Semitism. Suggestions to the effect that National Socialist anti-Semitism arose in toto from left-wing theorists represents a common trick that right-wing polemicists like Sherratt love to pull in order to blame-shift responsibility for the Holocaust onto the left.

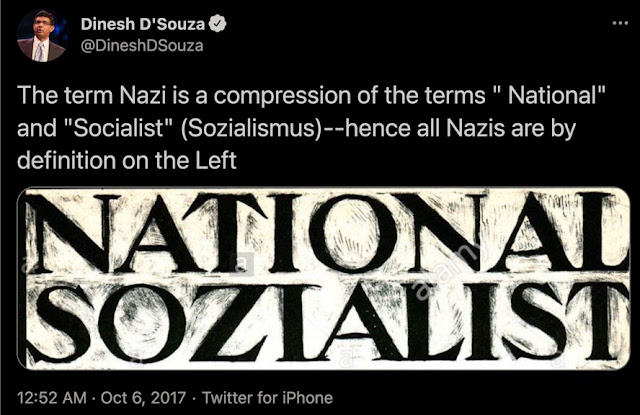

Sherratt’s book belongs amongst a growing number of polemical right-wing tracts attempting to blame the crimes of the National Socialist regime on the “socialist” left

This statement by Dinesh D'Souza is also a fair summary of Sherratt's book:

Against Hegel, regarded by Marx and Engels as an intellectual forerunner, Sherratt runs the following dated smear campaign:

Hitler laid the foundations of gleanings from other thinkers such as Hegel and Fichte while in his prison cell [no supportive citations]. One commentator noted that:

Hitler’s views articulated in Mein Kampf (‘My Struggle’), built in many ways upon more orthodox conservative German political theorists and philosophers. Hegel (1770-1831), for instance, had stressed the importance of a strong state ... and the existence of a ... [destiny] in history which justified war by superior states upon inferior ones. [quotation taken from Tansey and Jackson: Politics (The Basics) who give no supportive citation to justify their reading of Hegel, nor evince evidence of having ever read Hegel]

Hegel’s historical view of the formation of the state from ancient origins was, in garbled form, a favourite theme of Hitler’s and would often reappear in his orations.

Sherratt, Yvonne: Hitler's Philosophers (p. 22). Yale University Press. Kindle Edition.No actual evidence of Hegel stating his support for Realpolitik through war waged by stronger states against weaker ones is ever shown. The reason is that no such quotes exist, forcing authors who make such claims to make fictional “quotes” up instead, such as the old chestnut about the “march of God”. This allows baseless speculation to be passed off as indubitable fact. Nor does Sherratt demonstrate, using direct primary quotations, the existence of any direct intellectual influence of “orthodox conservative German political theorists and philosophers” in Mein Kampf. If Sherratt wanted to present such as case, she needed to have devoted at least a whole chapter to systematically arguing this point rather than passing an unsupported statement off as fact buttressed by little more than narrativistic “docudrama”. Nor does a secondary bibliographic citation to a review for beginners such as Politics (The Basics), a book purporting to be “a basic introduction to twenty-first century politics”, by authors who casually repeat hearsay while failing to demonstrate the slightest familiarity with Hegel’s original texts, add an iota of substance to Sherratt’s case.

Sherratt then proceeds to quote from one of Hitler’s ‘orations’ even though Hegel is nowhere mentioned in it. If she wanted to argue that Hegel is present “in garbled form” (Sherratt, p.22), she needed to have made a stronger case for it with a detailed side by side analysis of primary quotations from Hitler and Hegel rather than passing off vague and unsubstantiated insinuations as an open and shut case. Otherwise, it looks like the only thing “garbled” is the confused nonsense Sherratt presents as fact. It is all nothing new, and in the post-war anti-Hun intellectual environment, it was the sort of “march of God” fantasy that used to be all too common—post-war revisionist distortions about Hegel as the Ur-Kraut of German history, long ago thoroughly debunked, yet which Sherratt insists on reviving purely for the sake of her self-serving right-wing crusade.

Frederick Beiser, an unfailingly insightful commentator on Hegel and German idealism, summarises Hegel’s political views, and its wilful post-war misrepresentation by neoliberal polemicists such as Karl Popper, far better:

Given the pluralistic structure of Hegel’s state—its inclusion of intermediate groups and the whole realm of civil society—it should be clear that the common liberal criticisms of Hegel as a defender of absolutism, or as a forerunner of modern totalitarianism, are very wide of the mark. What is so unfair about these criticisms is that Hegel shares the liberal’s hatred of totalitarianism and develops his organic model of the state to prevent it. It was one of the chief aims of his organic state to avoid the ‘machine state’ of Prussian absolutism or French Jacobinism, where everything is controlled from above, leaving no room for local self-government...

Frederick Beiser: Hegel (The Routledge Philosophers)

Nor, as Richard J. Evans has pointed out, is it methodologically acceptable in academic historiography to conflate the Prussia of Hegel’s era (1770–1831) with either Imperial Germany after its unification under Bismarckian Prussia in 1871, or with the Wilhelmine Germany of WWI—let alone with National Socialist Imperialist Germany. To do so is to assume that ‘em bloody Krauts are all the same—always ‘ave been, always will be.

Evans is particularly critical of Sherratt’s allegation that Wagner’s operas are an artistic aestheticization of the traditional German love of murdering and torturing Jews:

Wagner was “perhaps the most virulent anti-Semite of them all. In some of his operas”, Sherratt asserts, “he turned Jew hatred into an aesthetic experience” [Sherratt, p.43]. Again, no evidence for this—to put it mildly, controversial—claim.

Evans: Review for Times Higher Education, 2013

Sherratt seems unaware that nineteenth-century figures like Wilhelm Marr, Eugen Dühring, Bernard Förster, and Adolf Stoecker were far more prominent anti-Semites than Wagner in his time, but all were fringe figures. It is all too easy to ignore the fact Friedrich Engels pilloried Dühring for his racist views, and Rudolf Virchow did much the same to Stoecker. A serious historian like Mark Roseman does not even mention Wagner in a roll-call of key nineteenth-century anti-Semitic German writers:

As with Sherratt, supportive citations are absent because such sweeping statements are completely fictitious. Another populist Occult Reich book concurs with Sherratt’s view of Wagner as an “intuitive magician” controlling world-destiny from beyond the grave in stating that:

Writing about the huge speculative popular literature on the Dritte Reich, Frank Lost tells us:

Sherratt further states without an ounce of support that Wagner, a friend of socialist anarchist Mikhail Bakunin, supposedly belonged to “a very different end of the political spectrum” from Karl Marx and Ludwig Feuerbach. Once again, despite her claims to the effect that the book is “carefully researched” and “meticulously referenced” she seems to be blissfully unaware of the profound influence of Feuerbach on Wagner:

Some authors have argued that there is therefore a continuity of intent stretching from writers such as Wilhelm Marr, Eugen Dühring and de Lagarde through to the Holocaust, but it seems extremely unlikely that Hitler’s precursors really conceived of the mass biological destruction of hundreds of thousands or millions of individuals.

In making grossly exaggerated unsupported claims demonising Wagner as the singular writer who provided the backbone to this fatal “continuity of intent”, Sherratt sinks to the level of the speculative kitsch of lurid Occult Reich books—first cousin to Nazi UFO conspiracy books. One such book alleging that Hitler had signed a “compact with the forces of evil” makes audacious claims to the effect that:Roseman, Mark: The Villa, The Lake, The Meeting: Wannsee and the Final Solution (p. 8). Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition.

Wagner described the Jews as ‘the devil incarnate of human decadence’ [no bibliographic citation] and called for ‘a Final Solution’ to ‘the Jewish problem’ [no bibliographic citation].

From section entitled Pagan Revivalism and Völkisch Christianity in The Nazi Occult War: Hitler's Compact with the Forces of Evil by Michael Fitzgerald (Arcturus Publishing Limited, 2013).

As with Sherratt, supportive citations are absent because such sweeping statements are completely fictitious. Another populist Occult Reich book concurs with Sherratt’s view of Wagner as an “intuitive magician” controlling world-destiny from beyond the grave in stating that:

Wagner provided the musical setting for Hitler’s vision of German global domination. His epic melodramas are a granite monument in music to the grandeur of Aryan superiority and sacrifice. Without Wagner’s Sturm und Drang (storm and stress) tempered with pastoral interludes, Nazism would not have acquired its mythic undertones.

Both Theodor Reuss, a practitioner of Tantric sex magick [sic], and Sar Peladan, the French writer on the occult, believe that Wagner was an intuitive magician.

From The Nazis and the Occult: The Dark Forces Unleashed by the Third Reich by Paul Roland.

Writing about the huge speculative popular literature on the Dritte Reich, Frank Lost tells us:

It does not add anything to the uncanny spell of such stories to pollute them with material that cannot be verified or, even worse, with pure lies coming straight out of the imagination of poor authors in search of quick money and fame. These made-up stories are usually rewritten in a thousand ways on the Internet, and everyone ends up adding their own personal touch or interpretation, feeding on each other as makeshift sources... Any book that dealt with Nazis and the occult, Satan, UFOs or secret treasures was assured to be sold at thousands of copies.

Frank Lost: Nazi Secrets—an Occult Breach in the Fabric of HistorySherratt follows the non-academic speculative methods of Roland or Fitzgerald in failing to adequately support sweeping speculations that get routinely blurted out without the slightest bit of support—speculations, which for all of their enthralling audaciousness, turn out to be completely fictitious right down to luridly titillating nonsense about “Tantric sex magick”. It is the sort of Occult Reich pseudo-history that David Luhrssen described in his excellent study of the Thule Society, Hammer of the Gods, as “pulp fiction in the guise of history”:

The Third Reich was so aberrant and, for many, so perversely intriguing, that irrational explanations have been eagerly and often carelessly embraced by popular audiences as supplement or substitute for the economic and political rationales of mainstream historians.

Luhrssen: The Hammer of the Gods, p.203It is to this very same base populism that Sherratt also sinks.

Sherratt further states without an ounce of support that Wagner, a friend of socialist anarchist Mikhail Bakunin, supposedly belonged to “a very different end of the political spectrum” from Karl Marx and Ludwig Feuerbach. Once again, despite her claims to the effect that the book is “carefully researched” and “meticulously referenced” she seems to be blissfully unaware of the profound influence of Feuerbach on Wagner:

|

| Dedication by Wagner of Art and Revolution to Ludwig Feuerbach “in grateful reverence” |

Wagner made it very clear that his anti-Judaism was a demand for Jewish assimilation, which in those days was considered the next logical step after emancipation.

|

| Richard Wagner called for the “Assimilation” of the Jews. From an original printing in German |

In this regard, Wagner and Marx were very much ideologically in step, and to conflate this assimilationism with a racially based eliminationism for the sake of running a right-wing polemic against the left is highly disingenuous. However, there is no possibility of such nuance to Sherratt: ‘em bloody Krauts are all Nazis—they’re all the same, they never change.

Sherratt goes on to claim that:

In Mein Kampf, Hitler also wrote of Wagner as one of the intellectual precursors of National Socialism for not only his music but his anti-Semitism struck a chord. Hitler's identification with Wagner was so profound that Hitler declared ‘to understand Nazism one must first know Wagner’.

Sherratt, Yvonne: Hitler's Philosophers (p. 30). Yale University Press. Kindle Edition.

This too is gross misinformation, since the alleged quote that goes “whoever wants to understand National Socialist German must know Wagner” is almost certainly fake. What Hitler actually wrote was this:

To these belong also the great fighters of this world, who, though not understood at present, nonetheless have carried out the fight for their ideas and ideals. They are those who some day will stand close to the heart of the people. To these belong not only the great statesmen but also the great reformers. Alongside Frederick the Great stands also Martin Luther as well as Richard Wagner.

Zu ihnen aber sind zu rechnen die großen Kämpfer auf dieser Welt, die, von der Gegenwart nicht verstanden, dennoch den Streit um ihre Idee und Ideale durchzufechten bereit sind. Sie sind diejenigen, die einst am meisten dem Herzen des Volkes nahestehen werden . . . Hierzu gehören aber nicht nur die wirklich großen Staatsmänner, sondern auch alle sonstigen großen Reformatoren. Neben Friedrich dem Großen stehen hier Martin Luther sowie Richard Wagner.

Adolf Hitler: Mein Kampf, p.232. My translation. Zentralverlag der NSDAP, Verlag Franz Eher Nachf., G.m.b.H.; Munich, 1943

Hitler vaguely implies through his name-dropping is that he wished to be remembered alongside three great German forebears. However, he never actually states that Wagner—nor Luther or Frederick the Great—were “intellectual predecessors” of National Socialism as Sherratt claims. Frederick was an enlightened monarch who was to pave the way for Prussia to grant emancipation to the Jews, and Wagner advocated assimilation of the Jews. As Evans has stated elsewhere:

Hitler never referred to Wagner as a source of his own antisemitism, and there is no evidence that he actually read any of Wagner’s writings.

Evans: The Third Reich in Power

Evans goes on in his criticism of Sherratt:

In ransacking all these authors for “anti-Semitic” quotes she reduces Nazism to the single aspect of anti-Semitism and ignores every contemporary context in which they were written. But the Jews were not the only “targets of Hitler’s wrath”; many more people, among them liberals, socialists, communists, homosexuals, gypsies and pacifists, were targets of his wrath as well.

Evans: Times Higher Education

The biggest problem is that Sherratt fails to realise that writing history from the perspective of 1940s Allied war propaganda is completely unhelpful. This is especially so when you consider that Allied anti-Hun propaganda represented a crude inversion of German war propaganda. For example, National Socialist propaganda alleged that hatred of Jews, pacifists, and other liberals was eternally written in the blood of true Germans. Allied war propaganda just reiterated that it was eternally written in the national character that Germans loved war and murdering Jews while hating peace and liberal ideals. Both the National Socialist propaganda and Allied propaganda saw the German national character as monolithic and eternally unchanging because it was determined by “blood and soil” rather than by socio-political and historical circumstance: “once a German—always a German”. Sherratt seems to think that by tipping the Swastika on its head and inverting German propaganda that it automatically makes her worthy of being awarded a medal for being a valiant anti-Nazi while firing up the thousand-year British Empire for eternal glorious battle against those “bloody Krauts”.

Once again, many of these issues are addressed by Evans in a public talk on German national identity. It is noticeable that Sherratt’s view of German national identity shares much in common with that of Margaret Thatcher, who at a meeting at Chequers on German unification in 1990 stated that the German Mind had been eternally marred by:

Angst, aggressiveness, assertiveness, bullying, egotism, inferiority complex, sentimentality, their obsession with themselves, their inclination towards self-pity, a longing to be liked, a capacity for excess, a tendency to overdo things....

Thatcher’s words are an elaboration of Lord Vansittart’s 1941 wartime propaganda book Black Record: Germans Past and Present:

In the book, Vansittart argued that the three elements of “German psychology” were “Envy, Self-pity and Cruelty” (Vansittart, p.4). Sherratt follows the same line of argument found in Vansittart and Goldhagen that the “German Mind” had forever been mired with a Cruelty all-consumed with psychopathic genocidal blood-lust. Vansittart went on:

...the remnants of the German conscience are easily satisfied by the drug of mechanical obedience to any order, however cruel. Prussianism, militarism, lust of world-conquest, Nazism—that sequence has made Germans the exponents of every variety of dirty fighting and foul play” (p.9).

Sherratt’s book constitutes the very epitome of this Thatcherite neoliberal and reactionary right-wing imperialist view that the “bloody Krauts” were an inferior race that needed to be exterminated by vast swarms of Spitfires and Lancasters as a reminder that “once a German—always a German”. This is why Sherratt devotes a whole book aimed at rekindling hate-filled notions found in Allied war propaganda asserting that the eternally immutable Nazi-German character had been exuded in everything Germans did and thought for centuries.

|

| Sherratt performs a thoroughly aggressive right-wing Thatcherite hatchet job on history. Cartoon of Margaret Thatcher by Chris Madden |

The great irony is that Theodor Adorno, on whom Sherratt published a book entitled Adorno’s Positive Dialectics, sternly warns against the ongoing perpetuation of such war propaganda stereotypes in his post-war essay, “On the Question: What is German?” (Auf die Frage: Was ist Deutsch? From p.691–701 of Suhrkampf complete works; Kulturkritik und Gesellschaft II):

The formation of national generalisations, however—common in the abominable war jargon that opines over the Russians, the Americans, and certainly also over the Germans—obeys a reifying consciousness, one that is not quite true to experience. They confine themselves within these stereotypes, which directly absolve them from thinking. It is uncertain if something like The Germans, or The German, or anything similar in other nations, even exists. The True and Better in every nation is probably rather what does not fit the collective subject, possibly that which withstands it. In contrast to that, the formation of stereotypes promotes collective narcissism. That with which one identifies as the essence of one’s insider-group will unwittingly be good; whereas that of the outsider-group—the Other—bad. Likewise, the image of the Germans fares contrariwise amongst that Other. However, since under National Socialism, the ideology of the primacy of the collective subject at the expense of the individual wreaked the most extreme disaster, there is doubly reason to be wary in Germany of a relapse into self-adulatory stereotypes.

Die Bildung nationaler Kollektive jedoch, üblich in dem abscheulichen Kriegsjargon, der von dem Russen, dem Amerikaner, sicherlich auch dem Deutschen redet, gehorcht einem verdinglichenden, zur Erfahrung nicht recht fähigen Bewußtsein. Sie hält sich innerhalb jener Stereotypen, die von Denken gerade aufzulösen wären. Ungewiß, ob es etwas wie den Deutschen, oder das Deutsche, oder irgendein Ähnliches in anderen Nationen, überhaupt gibt. Das Wahre und Bessere in jedem Volk ist wohl vielmehr, was dem Kollektivsubjekt nicht sich einfügt, womöglich ihm widersteht. Dagegen befördert die Stereotypenbildung den kollektiven Narzißmus. Das, womit man sich identifiziert, die Essenz der Eigengruppe, wird unversehens zum Guten; die Fremdgruppe, die anderen, schlecht. Ebenso ergeht es dann, umgekehrt, dem Bild des Deutschen bei den anderen. Nachdem jedoch unterm Nationalsozialismus die Ideologie vom Vorrang des Kollektivsubjekts auf Kosten von jeglichem Individuellen das äußerste Unheil anrichtete, ist in Deutschland doppelt Grund, vorm Rückfall in die Stereotypie der Selbstbeweihräucherung sich zu hüten.

Adorno: Auf die Frage: Was ist Deutsch? From p.691. My translation.

It is unsurprising that Sherratt is unfamiliar with this essay, since no English translation has been published, and based on what can be gleaned from any of the books she has written, she appears not to read German, thus making the vast majority of Adorno’s writing inaccessible to her. If Sherratt did read German she would have found Adorno sternly rejecting collective stereotypes about “The Germans” as merely promoting narcissistic nationalistic stereotypes across the board.

This is why the Goldhagen thesis appeals to Sherratt so profoundly. Sir Richard J. Evans tells us

Goldhagen argues that Germans killed Jews in their millions because they enjoyed doing it, and they enjoyed doing it because their minds and emotions were eaten up by a murderous, all-consuming hatred of Jews that had been pervasive in German political culture for decades, even centuries past (pp. 31– 2 [of Hitler’s Willing Executioners]). Ultimately, says Goldhagen, it is this history of genocidal antisemitism that explains the German mass murder of Europe’s Jews, nothing else can.

This is a bold and arresting thesis, though it is not new. Much the same was said during the Second World War by anti-German propagandists such as Robert Vansittart or Rohan Butler, who traced back German antisemitism—and much more—to Luther and beyond; a similar argument was put forward by the proponents of the notion of a German ‘mind’ or ‘character’ in the 1960s, and by William L. Shirer in his popular history of Nazism.Evans: Rereading German History: From Unification to Reunification 1800-1996 (pp. 150-151). Taylor and Francis. Kindle Edition.

The end result of Sherratt’s gratuitous perpetuation of these sorts of war propaganda stereotypes is that she constantly paints black-and-white caricatures of what she regards as proto-Nazi Kraut-Think, with its allegedly immutable antisemitism, racism, militarism and authoritarianism, that Sherratt assumes has been all-pervasive in the “blood and soil” of “The Germans” throughout history. She even finds evidence of such Kraut-Think in Immanuel Kant. Sherratt alleges that Hitler quoted Kant in Mein Kampf:

[Hitler] wrote Mein Kampf, in which he outlined his atrocious beliefs... Hitler quoted from the founding fathers of the German tradition such as Immanuel Kant...

Sherratt, Yvonne: Hitler's Philosophers (p. 2). Yale University Press. Kindle Edition.

Since Sherratt fails to give us the specific citation to the alleged quote in question, I looked up the original German text of Mein Kampf myself (Zentralverlag der NSDAP, Frz. Eher Nachf., G.m.b.H., Munich, 1943). I could not find even a single quotation from Kant anywhere in the book—nor for that matter in his Table Talk, Speeches 1932-1945, Speeches 1921-1941, Speeches 1925-1945, or Zweites Buch.

Sherratt further insinuates that Kantian ethics were used by Adolf Eichmann to justify the mindless obedience to the killing apparatus of the Final Solution on the basis of observance of mindless deontological duty. Sherratt evinces little awareness that Eichmann’s claims that he was forced to obey a decisive Hitler Order to commit mass genocide has been demonstrated to be a fiction he concocted in his own defence only after his capture (see Peter Longerich for a detailed discussion)—no evidence exists that such a decisive Hitler Order was ever issued, and those in the “polycratic jungle”, like Heydrich and Eichmann, were likely taking their own initiatives in ordering mass murder. This is what Arendt had to say in her report of the Eichmann trials:

[Eichmann] suddenly declared with great emphasis that he had lived his whole life according to Kant’s moral precepts, and especially according to a Kantian definition of duty. This was outrageous, on the face of it, and also incomprehensible, since Kant’s moral philosophy is so closely bound up with man’s faculty of judgment, which rules out blind obedience. ... Judge Raveh, either out of curiosity or out of indignation at Eichmann’s having dared to invoke Kant’s name in connection with his crimes, decided to question the accused. And, to the surprise of everybody, Eichmann came up with an approximately correct definition of the categorical imperative : “I meant by my remark about Kant that the principle of my will must always be such that it can become the principle of general laws” (which is not the case with theft or murder, for instance, because the thief or the murderer cannot conceivably wish to live under a legal system that would give others the right to rob or murder him). Upon further questioning, he added that he had read Kant’s Critique of Practical Reason. He then proceeded to explain that from the moment he was charged with carrying out the Final Solution he had ceased to live according to Kantian principles, that he had known it, and that he had consoled himself with the thought that he no longer “was master of his own deeds”, that he was unable “to change anything”. What he failed to point out in court was that in this “period of crimes legalized by the state”, as he himself now called it, he had not simply dismissed the Kantian formula as no longer applicable, he had distorted it to read: Act as if the principle of your actions were the same as that of the legislator or of the law of the land—or, in Hans Frank’s formulation of “the categorical imperative in the Third Reich”, which Eichmann might “Act in such a way that the Führer, if he knew your action, would approve it”. Kant, to be sure, had never intended to say anything of the sort; on the contrary, to him every man was a legislator the moment he started to act: by using his “practical reason” man found the principles that could and should be the principles of law. But it is true that Eichmann’s unconscious distortion agrees with what he himself called the version of Kant “for the household use of the little”.

Arendt, Hannah. Eichmann in Jerusalem—A Report on the Banality of Evil. (pp. 135-136). Penguin Publishing Group. Kindle Edition. My emphasis in red

Compare this with Sherratt’s distorted account of this incident: