Why is music written at all? Is it not a romantic feeling which makes you listen to it? Why do you play the piano when you could show the same skill on a typewriter? Why do you sing? Why play the violin or the flute?

Style and Idea P321 (Edited by Leonard Stein) University of California Press, 1975.

In his later years, as Schoenberg came to increasingly feel at home with twelve-tone composition, his music started to sound more and more like Brahms. I have already mentioned that both of these composers wrote the same number of string quartets, but they also wrote the same number of chamber symphonies and violin concerti. Even in his earliest twelve-tone compositions, you notice the first beginnings of this trend towards sounding more like Brahms. Schoenberg's very first orchestra twelve-tone composition is his Variations for Orchestra, just as Brahms' first large scale orchestral work is his St Anthony Choral Variations. The Variations by both composers are in the Brahmsian "developing variations" style, and both go through slow-movement like and scherzo-like sets of variations before ending in triumphant finales.

If you further listen to the theme that opens the start of the Ode to Napoleon, Opus 41 (1942), it even resembles that of the opening theme of the finale of the Brahms Piano Quartet in G minor, that Schoenberg orchestrated. The Schoenberg Piano Concerto even has four movements just like the Brahms Second. The Schoenberg Piano Concerto also begins with a Viennese waltz, which Emmanuel Ax calls supremely Brahmsian. Schoenberg write in a 1946 essay, in which he quotes the opening waltz of the Piano Concerto and the Andante Theme from the Violin Concerto:

Assuming that a composer is at least entitled to like his themes (even though it may not be his duty to publish only what he himself likes), I dare say that I have shown here only melodies, themes, and sections from my works which I deemed to be good if not beautiful.

Heart and Brain in Music, from Style and Idea P74

It is not the heart alone which creates all that is beautiful, emotional, pathetic, affectionate, and charming; nor is it the brain alone which is able to produce the well-constructed, the soundly organised, the logical, and the complicated. First, everything of supreme value in art must show heart as well as brain.

Heart and Brain in Music, from Style and Idea P75

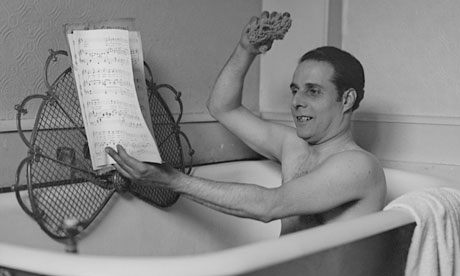

Given this, I always find it exceedingly curious that Berg's Violin Concerto has become a mainstream staple in the concert hall, but that the Schoenberg Violin Concerto has yet to be as warmly embraced by the public. The reason is that Schoenberg's Violin Concerto Opus 36 (1936) has themes in it that are much more singable than the Berg. By singable, I mean in the sense that you could still sing them in the bathtub after drinking too much champagne. As dearly as I love the Berg Violin Concerto, if I tried to sing anything from it in the bathtub after imbibing too much wine, I doubt I would be able to. In fact, the main themes in Schoenberg's Violin Concerto are easily more singable than anything from Verklärte Nacht.

In fact, Schoenberg once wrote, in a letter to Hans Rosbaud, dated 12th May, 1947:

But there is nothing I long for more intensely (if for anything) than to be taken for a better sort of Chaykovsky—for heaven's sake: a bit better. but really that's all. Or if anything more, then that people should know my tunes and whistle them.

The truth of this really came home to me when I first listened to Hilary Hahn's superb recording of the Schoenberg Violin Concerto coupled with the Sibelius Violin Concerto.

One hearing both works on the CD, one after the other, it became apparent to me that the extremely Brahmsian sounding main theme which opens the Schoenberg Concerto is actually immeasurably more singable than anything in the accompanying Sibelius Concerto, let alone anything in the Berg Concerto. Even the theme of the Schoenberg Andante movement is more singable than anything in the Berg or Sibelius concerti.

There is even a sense of playfulness in the finale that strongly resembles the finale of the Brahms Violin Concerto. Admittedly, this proves deceptive, since the ending of the Schoenberg Concerto is more post-Mahlerian than Brahmsian. Once again, it ends with an apocalyptic thump, which knocks the imaginary hero off horseback, in a manner that recalls the end of the Mahler Sixth.

Not only that, but it should be remembered that Joseph Joachim complained that Brahms wrote him no real tunes for his violin concerto, and that the closest thing to anything resembling a tune in the whole work had been given away to a solo oboe in the slow movement. Even that solo oboe theme is hardly conducive to singing in the bathtub. This means that the Schoenberg Concerto is, in some ways, even more deeply Brahmsian in its intensely singable lyricism than the Brahms!

The widespread acceptance of Berg's Violin Concerto seems largely based on the fact that audiences have tricked themselves into falsely believing that Berg's music is more singable and accessible than Schoenberg and Webern's. Because they believe this to be so, their anxieties melt away, and it becomes so, in a self-fulfilling prophecy. It goes to show that the fears which audiences harbour about the Second Viennese School are largely imaginary. People should instead relax more and learn to sing their Schoenberg in the bathtub:

The bizarre thing is that despite this, you still get these hardheaded killjoys who have stubbornly convinced themselves in believing that Berg's music differs from Schoenberg and Webern's in that it is supposedly more "expressive". I could hardly think of anything further from the truth. This is another imaginary stereotype about the Second Viennese School that needs to be banished from people's minds. I think that Hilary Hahn's beautiful recording does an excellent job of doing precisely that, making it mandatory listening. I even prefer her performance to that by Louis Krasner and Dimitri Mitropoulos.

Only Rudolf Kolisch accompanied by Rene Leibowitz has additional special insights to offer:

Most importantly, Kolisch gives a deeply lyrical performance that is a far cry from one these modern performances that tries desperately hard to kill the Brahmsian lyricism in order to force Schoenberg to sound like some Darmstadt Generation composer. There is a strong argument to be made for taking the music of the Second Viennese School away from modern music specialists. In fact, given that Schoenberg was already 22 years old when Brahms died in 1897, it makes it high time to stop calling the music of a man born and raised in the Victorian era, modern!

When Schoenberg said a composer should "follow the row" and then carry on composing "as before"*, he really meant it. The twelve-tone system is a method of composition, rather than a style of composition. This is something that Pierre Boulez discovered to his shock, and he has even gone so far as to rail against Schoenberg for the "Romantic decadence" of his twelve-tone compositions. Schoenberg is definitely the most deeply traditionalist of all twentieth century composers. Since Schoenberg took up American citizenship, this means he easily takes the title of the American Brahms off Samuel Barber. When you consider Schoenberg was born in Vienna, unlike the Hamburg born Brahms, this makes Schoenberg more Viennese than Brahms too. Schoenberg remains the very epitome, pinnacle, and apotheosis of Viennese Romanticism.

By now, those who have followed me through this journey into the musical world of Schoenberg and the Second Viennese School, will have found much to that is genuinely beautiful, moving and even plain enjoyable. I am of the belief that, like Mahler, the Second Viennese School will gradually be embraced by the wider musical public. I am not going to go through every composition by Schoenberg one by one. I think that should be superfluous by now. This is not to say that I expect the reader will like everything by Schoenberg—or for that matter, by any other composer. There are works by Mozart that I have, for reasons unknown, never really been able to "get into". As for other works that readers may like to go on to explore, I have already mentioned the Piano Concerto and the Ode to Napoleon. Another suggestion I have is the late string Trio, Opus 45 – an account of a near death experience. Once you have familiarised yourself a bit more with the idiom, I suggest the Variations for Orchestra (listen for how the row for this work contains the name of BACH in it, with Schoenberg literally shouting out his name in joyous triumph at the end). I also suggest going back and trying the moon crazed Pierrot Lunaire, and the celestial Jakobsleiter.

Yet, there is one more work I have yet to even mention – a work that Schoenberg regarded his opus magnus, despite it being left incomplete at his death. If other mature works by Schoenberg are deeply Brahmsian, this one, on the contrary is extremely Wagnerian. I will devote my next, and last post, in this series to this work.

* See 7.21 "Wiesendgrund" (December 1950) p337 in A Schoenberg Reader: Documents of a Life

No comments:

Post a Comment