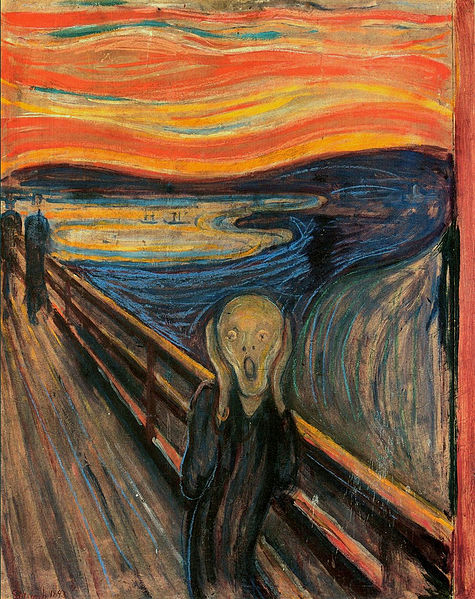

Far from being unprecedented, this is really just a continuation of a trend found in Mahler's symphonies, particularly the Sixth, Ninth, and Das Lied von der Erde, which struggle with the subject of death. Stylistically, Schoenberg enters into an Angst-ridden world increasingly reminiscent of paintings by Edvard Munch:

The first two movements are the easiest to understand. Start with the first piece, and don't go on to the next piece until you "get" the first one. Right from the opening of the first piece, there is a brooding lyricism in the music, that extends into the second piece, which is thoroughly Viennese. As in Schubert's Winterreise, these moments of intense lyricism seem more like an ironic counterpoint to the unremitting bleakness of the work. The finale is the most challenging piece, as it so utterly chaotic in its apocalyptic darkness, with the ending granting not an iota of relief. This descent into an increasing dark and chaotic emotional world becomes an increasingly common characteristic of Schoenberg's music from around this time onwards. This sense of chaos in a world of so-called free atonality is highly reminiscent of the early abstract canvasses by Wassily Kandinsky:

Just as Kandinsky's later canvasses have a greater sense of order to them, so too did Schoenberg too find a path to order out the chaos of the dark, tormented expressionist world of his free atonal compositions.

There were several reasons why I chose this recording. For a start, it is coupled with Beethoven and Schumann. It avoids recommending a CD full of other Schoenberg, which you may not be ready to hear yet. It also rightfully places Schoenberg in continuity with other Viennese composers before him. Arrau has little fear of unleashing the emotional power of these pieces.

Mitsuko Uchida is also very good, but Arrau plumbs greater poetic depths.

The recording by Maurizio Pollini is also excellent, and remarkably expressive – in the first of the Three Pieces, surprisingly, more so than Uchida:

In the meantime, the unremitting bleakness of this music will take the listener some getting used to. This is truly music that you must learn to love. Careful, repetitive listening will reward the listener amply, and it will open doors for you. For example, you may more readily understand the fantastic darkness of the nightmarish world of Pierrot Lunaire particular that of Finstre, schwarze Riesenfalter, which occupies the same dark and chaotic world as the Three Pieces:

Finstre, schwarze Riesenfalter

Töteten der Sonne Glanz.

Ein geschlossnes Zauberbuch,

Ruht der Horizont - verschwiegen.

Aus dem Qualm verlorner Tiefen

Steigt ein Duft, Erinnrung mordend!

Finstre, schwarze Reisenfalter

Töteten der Sonne Glanz.

Und vom Himmel erdenwärts

Senken sich mit schweren Schwingen

Unsichtbar die Ungetume

Auf die Menschenherzen nieder...

Finstre, schwarze Riesenfalter.

Sinister black moths of the night

Have extinguished the glory of the sun.

And the horizon seems a spellbook

Smeared with ink all night.

They exude an occult incense

A perfume stifling memory.

Sinister black moths of the night

Have extinguished the glory of the sun.

And from heaven earthward

Gliding down on leaden wings

The invisible monsters

Descend upon our human hearts...

Sinister black moths of the night.

The translation is mine, based partly on the German translation used by Schoenberg, but also partly on the original French text. The German translation is very liberal, and where the original French is much easier to translate into English I have preferentially used that. I would recommend that the reader familiarise themselves through and through with the Three Pieces before moving on to Pierrot Lunaire.

However, listeners familiar with late Mahler, who have followed this series of threads so far, should find little to trouble them technically with the atonality of the Three Pieces. It is rather their emotional darkness that proses the real difficulty. If you do overcome whatever difficulties encountered on first hearing, and grow to love these landmark works of twentieth century music as I have, you will emerge from it able to appreciate the whole of the rest of the music of the Second Viennese School with ever growing confidence and ease. In fact, it is a journey of discovery you will relish.

* Unlike with his previous Opus 10 composition (in F sharp minor), for the Opus 11 piano pieces, Schoenberg abandons a key signature for the first time.

No comments:

Post a Comment