|

| Pelleas and Melisande by Edmund Blair Leighton |

It takes a real virtuoso orchestra to pull this score off, so as to make it sound as as fittingly sumptuous as it deserves to. Schoenberg makes tremendous demands of the orchestra including those marvellous—as they are notorious—trombone glissandi. When it all comes together, the fantastic evocation of Medieval castles with their mysterious towers and sinister dungeons, capped off with its Wagnerian evocation of a quasi-mystical erotic religion of love—it is all precisely what Maeterlinck's world is all about.

Alban Berg, who had a fascination bordering on obsession with Pelleas, saw this symphonic poem as a kind of one movement symphony with an opening section like a symphonic opening movement, other sections being like the scherzo, the slow movement and finale. However, rather than being clearly separated movements, all have been combined into one single movement.

Part I: First-Movement Sonata Form

Introduction

First group of themes: Golaud marries Melisande

Transition

Second group of themes: Pelleas

Codetta: awakening of love in Melisande

Short recapitulation

Part II: Scherzo with Episodes

Scherzo: scene at the fountain in the park

Episode 1: scene at the tower

Episode 2: scene in the vaults

Part III: Slow Movement

Introduction: fountain in the park

Love scene

Coda: intervention of Goland, death of Pelleas

Part IV: Recapitulatory Finale

Recapitulation of introduction to first movement

Recapitulation of principal theme of first movement

Recapitulation of love theme

Entrance of serving women and Melisande's death

Epilogue: further recapitulation of themes

Although Schoenberg approved of Berg's analysis, this is only one way of looking at this work—something Berg himself probably knew. An easier way of looking at it may be to think of it as being an extended sonata form structure that expands on the form of the Tristan overture by forming a central section that functions like a development section. However, the development section is itself divided into a scherzo-like and slow-movement-like episodes. The way the slow-movement like section climaxes is strikingly similar to the climax of the Tristan overture, with the ardent climax of unbridled passion, culminating in the death of Pelleas. Only here the climax is abruptly cut short by the third and final intrusion of the Fate Leitmotiv. I would summarise things like this:

Exposition of Leitmotivs

Development I: Scherzo like section

Development II: Slow movement like section

Recapitulation of Leitmotivs and Coda

As with Wagner, there are only a limited number of leitmotifs in the work which undergo development during the course of the work. This really only undermines the feeling that this is a one movement symphony which retains individual "movements" within it. The great strength of this work is in the way Schoenberg has absorbed Wagner's Leitmotiv technique and spiced it up with a Brahmsian classical symphonic way of thinking. It brings a sense of logic and unity to the highly problematic form of the symphonic poem in a way that I find deeply satisfying – far more so than with in any other example of the symphonic poem I can think of, by any other composer. It is easy to see how you can get obsessed, like Berg did, by this endless fascinating masterpiece.

Despite this, you may find misguided comments such as those by Walter Frisch, who writes about Pelleas:

We sense Schoenberg struggling to reconcile programmatic and thematic-formal demands. Despite compositional awkwardness, the sextet easily convinces us of its status as a masterpiece. Pelleas und Melisande fails to do so; it seems bloated, its shortcomings more exposed.

The Early Works of Arnold Schoenberg 1893-1908 (University of California Press, 1993)Frisch pats himself on the head for being much more clever than Berg by "discovering" that the work fails to follow the strict architectural plan of a classical textbook symphony (oh my, what a surprise!). In other words, Frisch wants us to know that because Schoenberg is a bad boy for using Wagnerian styled leitmotivic compositional methods rather than following "proper" textbook sonata form rules—derided by Busoni as "sonata boxes". It is tantamount to saying that Wagner is symphonically unconvincing merely for failing to use classical textbook symphonic forms: if it doesn't fit into a sonata box, ripe for lazy analysis, toss it out.

As for sounding bloated, in the hands of a conductor, who – like Frisch – fails to "get" this work, it certainly will sound bloated: Karajan is a case in point. The sad thing is that you actually read reviews by fools praising Karajan's catastrophically bloated misrepresentation of this wonderful work. For some devotees, it seems that Karajan can "do no wrong". The reality is that Karajan's "advocacy" of Pelleas through his misguided recording has done more harm to the reputation of this work than all of Schoenberg's enemies combined. Who needs enemies when you have "friends" like Karajan and Frisch.

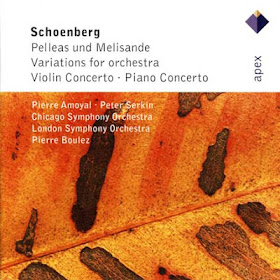

Fortunately, there are a couple of highly recommendable recordings of Pelleas by conductors who are immeasurably better advocates than these. Even its own day, Pelleas eventually came to enjoy success in the hands of advocates such as Oskar Fried, Wilhelm Furtwängler and Otto Klemperer. The first place to start today is with Pierre Boulez and the Chicago Symphony orchestra (recorded for Erato):

The Chicago Symphony make a glorious noise. Boulez is as good in this score as he is in Wagner – with all the passion and romance you could ever wish for. It is a pity that the Erato sound engineers failed to capture a less murky and boxy sound.

The other recording I can recommend highly is the Barbirolli with the New Philharmonia Orchestra, which can be found attractively coupled with Metamorphosen by Richard Strauss in a 1994 transfer.

Both the Chicago Symphony and the New Philharmonia are wonderful virtuoso orchestras that seem to relish the challenge of this work. They are both a joy to listen to. Barbirolli is hardly a name you associate with Schoenberg, but you sense that his heart is in this score. This can only be downloaded in the lossy MP3 320 format from Classicsonline (at least it is 320 kbs resolution, and not the 256 kbs that Apple-iTunes still condescend to). I suspect that this is a Kingsway Hall recording. The EMI sound engineering team, as often during this era, do an amazing job.

There is also a newer transfer of the Barbirolli Pelleas from 2006:

CD transfer sounds improved out of sight between 1994 and 2006. The good thing about the 2006 release is that it comes with the Schoenberg orchestration of the Brahms Piano Quartet Nr 1. The downside is that it comes with a rather lame Verklärte Nacht from Barenboim, who was only just practising his conducting at the time. This is the worst things about collecting Schoenberg - you end up with being forced to buy countless second rate recordings of Verklärte Nacht. As for the First Chamber Symphony, I hope to discuss this work at a later date. I would strongly advise against jumping unprepared from Pelleas to the First Chamber Symphony.

The most recent recording I can enthusiastically recommend comes from Jukka-Pekka Saraste and the West Deutsche Runkfunk (WDR) Symphony Orchestra Cologne:

When I lived in Cologne back in the mid-1990s, I heard them at the Phiharmonie a few times. Back then they were good, but since then they have grown into a remarkable orchestra that stands comparison with the finest. They prove more than up to the challenge of Pelleas to the point that they compare favourably to the Chicago and New Phiharmonia orchestras at their peak. This new recording can be downloaded as a lossless FLAC file from Prestoclassical. The sound engineering is superb, making this an excellent all round choice for audiophile's who value great music making.

The audophile's first choice amongst recordings is going to be the high-end recording of the Duisburg Philharmonic under the Jonathan Darlington.

This comes in a spectacular sounding 24/192 recording, which is ideal for showcasing the rich orchestra tapestry of this sumptuous score. It can be downloaded from the Linn website. The performance is also surprisingly good, even if they are hardly the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Darlington is a very sympathetic interpreter.

Also getting an honorary mention is Robert Craft on Naxos:

There are a couple of vintage recordings worthy of mention too. The first of these comes from Dimitri Mitropoulos with the New York Philharmonic in 1953, available from Music & Arts:

This can be downloaded as a FLAC file from Prestoclassical. As to be expected, this is an absolutely superb performance.

The second historical recording comes from Hermann Scherchen with the WDR Orchestra, but this is out of print.

It can currently only be downloaded from iTunes which means that it is sadly only available in a lossy format - in the unbelievably primitive 256 kbs resolution still offered by iTunes. It seems when it comes to audio sound reproduction Apple lives in the stone age. Hopefully, someone will one day reissue an improved remastering in an acceptable modern format.

The choice of which recording you pick should be determined by the coupling (or lack thereof) you get with it. I think that this work is best heard together with Wagner or Strauss. I recommend against jumping from Pelleas straight into the deep end of Erwartung, or the concerti for Piano and Violin. Nor is Boulez a good advocate of the Variations for Orchestra (a work Boulez has openly expressed contempt for), and his Pelleas is surprisingly much more committed. In fact, Ertwartung is a work I myself have never come to grips with. I like nearly all of Schoenberg's works, but this one has curiously always eluded me. I probably need to listen to a bit more closely, and I am sure one day I will "get" it. However, if Erwartung fails to excite you like Pelleas, that is quite all right. Put in in your "too hard basket" and come back to it much later.

In due course, I will gradually guide those still discovering Schoenberg through more mature works by Schoenberg and the Second Viennese School. I will choose works that are remarkably accessible, and hope to surprise some listeners as to just how richly Romantic, almost frankly Brahmsian, later Schoenberg becomes. In a sense, Schoenberg is the vigorous reaction that you elicit when you mix Wagner and Brahms. And, if Schoenberg once described Brahms as a radical dressed as a conservative, then Schoenberg is a traditionalist dressed as a radical.

No comments:

Post a Comment