A Review of Blood and Iron: The Rise and Fall of the German Empire 1871–1918 by Katja Hoyer

Amazon Kindle eBook edition (the edition used for the review)

ASIN : B08R9DKRV1

Publisher : The History Press (14 January 2021)

Print length : 224 pages

Hardcover : 256 pages

ISBN-10 : 0750996226

ISBN-13 : 978-0750996228

There is always a reason one reads a book. There is always a path that leads there and a story behind how one set out on the journey that led you there. Readers might know I am still working slowly on a book on Richard Wagner, written more from the perspective of historian than musicologist, art critic, or opera enthusiast. The reason for reading Katja Hoyer's book was simple: because it covered the historical period of Richard Wagner's lifetime (1813-1883), which strongly overlaps with that of Bismarck (1815-1898). Even though Hoyer's book focuses on the period from 1871-1918, a lot of the background starting around the time of the Napoleonic Wars is deftly covered.

A basic tenet of a historian's approach is that people are the product of history and therefore to properly understand 19th-century figures like Wagner or Bismarck, one must place them in historical perspective. Yet for all of that, the focus of discussion tends to get dragged back to the National Socialist era in the next century, which begs the question as to whether that is even relevant to such 19th-century cultural figures. As previous discussions on this have pointed out, the issue at stake in controversies around the so-call Sonderweg ("special path") concept, is whether there is a direct causal link between German social history of the 19th-century (or earlier) and the events of the early 20th-century.

Previous extreme versions of the Sonderweg ("special path") thesis of German exceptionalism have argued that Martin Luther poisoned the German Mind, brainwashing it into a mindset of universal obsequiousness towards authoritarianism and genocidal Jew-hatred, thus making the rise of Hitler a historical inevitability. The arch of the sweep of this extreme Sonderweg was several centuries long. This Luther-to-Hitler thesis originated in 1940s anti-Hun propaganda, and post-war historians have altogether shunned it as being too extreme. That has not stopped pop-historians like William Shirer and Daniel Goldhagen from writing best-sellers that sensationally revive such theories while professional historians struggle to write rival best-sellers that discourage the public from reading such populist narratives. Meanwhile, others have written books that push a rival Wagner-to-Hitler Sonderweg narrative, shortening the arch of the Sonderweg to only the 19th-century. Despite enjoying massive street-cred, this too enjoys precious little support among professional historians for simply being too grotesquely reductivistic.

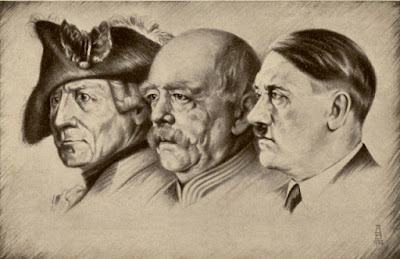

Interestingly, pre-20th century British historians did not see German history as a neat teleological straight line of a Sonderweg pointing inexorably to the rise and triumph of a Hitler. A good example is the 1858 biography of Frederick the Great of Prussia by Thomas Carlyle. It was only with the advent of the two world wars of the 20th-century that propagandists suddenly claimed to be able to "see" how the peculiarities of German history "obviously" lead it down the path of an inevitable march towards Hitler. Everything in German social and cultural history from Luther, Frederick the Great, Hegel, Wagner, Bismarck or Nietzsche suddenly became incontrovertible evidence of the spectacular "obviousness" that the German Mind had been brainwashed with "proto-Nazi" ideology for generations, or even centuries before the rise of Hitler. This has cast a long shadow over the study of German history.

It did not help that the National Socialist view of history portrayed the "Great Men" of German history as giants upon whose shoulders they themselves stood and who helped pave the providential "special path" (Sonderweg) towards the pinnacle of German history in the rise of Hitler. Non-historians still uncritically accept such propaganda as gospel, and it forms the basis of the layperson's view of German history. However, historians are downright sceptical about such gushingly self-adulatory "Great Man" historiography. Such propagandist claims as to the existence of a singular sweep of grand determinism spanning the centuries make historians cringe. And the fact that the National Socialists believed it gives us precious little reason to march blindly in their footsteps: as with all propaganda, it is just too reductivistic.

Since the late 1980s, the whole Sonderweg thesis has almost completely been discarded by professional historians. Interestingly, the Sonderweg thesis was sunk mostly by non-German

historians and only a dwindling old-school clique of ageing German historians

still clings to increasingly watered-down vestiges of this dying thesis of German

exceptionalism. For a lengthy critique of this sort of thing I refer the reader to

the discussion by Sir Richard J. Evans entitled "Whatever Became of the

Sonderweg?" in Rereading German History where he takes Hans-Ulrich Wehler (1931-2014) to task for his attempts to resuscitate the dying vestiges of the Sonderweg concept with a desperate spin of his prayer-wheel:

What does Wehler come up with to replace Bonapartism as a characterization of the Bismarckian regime? He turns his Weberian prayer-wheel and comes up with a new paradigmatic super-weapon: charisma. Bismarck, argues Wehler, was a classic example of the charismatic leader in the Weberian sense: he was extra-historical and unforeseeable, he depended on a ‘charismatic community’ of devoted followers... Of course Bismarck had enormous prestige, but to describe it as charisma elevates it to the super-historical and implies the abandonment of a structural explanation for the Sonderweg in favour of a personalistic one.

Evans, Richard J. Rereading German History: From Unification to Reunification 1800-1996 . Taylor and Francis. Kindle Edition.

Katja Hoyer's Blood and Iron is by no means the first post-Sonderweg account of 19th-century German history. For example, there is the excellent example from David Blackbourn in his History of Germany 1780-1918. There is also The Pursuit of Power: Europe 1815-1914 by Sir Richard J Evans himself. Although it submerges German history into European history, it emphasises parallels between German and Italian unification.

To be avoided at all cost is Christopher Clark's bizarrely anachronistic Iron Kingdom. Just in its Introduction, he resuscitates an ancient model of the Sonderweg based on an outdated interpretation of Hegel (1770-1881) claiming that he brainwashed the German Mind with a proto-Nazi authoritarian statist ideology by preaching that the "the state is the march of God through the world", where the Prussian state was worshipped as the "Holy Grail". A digital search in Hegel's complete works finds no instance of Hegel referring to the Prussian state as the "Holy Grail": this claim is pure fiction. The result is an extreme view, dating the origins of the Sonderweg way back to the Kingdom of Prussia around 1820, around the publication of Hegel's Elements of the Philosophy of Right. It is a Hegel-to-Hitler Sonderweg that looks more like something from the 1960s than 2009 (a view that looked stale by the 1980s and positively dated by the 1990s). Clark evinces exasperating unfamiliarity with the voluminous literature demolishing the Sonderweg concept, not to mention the abandonment of such dated Hegel readings over the same period (for a more modern view of Hegel see Knowles: Hegel and the Philosophy of Right).

More convincing is Shelly Baranowski's study of the longue durée of German imperialism about which Evans wrote in his review of her Nazi Empire: German Colonialism and Imperialism from Bismarck to Hitler:

A few decades ago, historians searching for the longer-term roots of Nazism’s theory and practice looked to the ruptures and discontinuities in German history: the failed revolution of 1848; the blockage of democratic politics after unification in 1871; the continued dominance of aristocratic elites over a socially and politically supine middle class; the entrenched power of the traditionally authoritarian and belligerent Prussian military tradition—in short, everything, they argued, that had come by the outbreak of the First World War to distinguish Germany from other major European powers and set it on a ‘special path’ [Sonderweg] to modernity that ended not in the creation of a democratic political system and open society to go with an industrial economy, but in the rise and triumph of the Third Reich. Such arguments were discredited by the 1990s, as it became clear that imperial Germany’s middle classes had been far from supine, its political culture was active and engaged, and its aristocratic elites had lost most of their power by the outbreak of the First World War. [...]

But if there was no domestic ‘special path’ [Sonderweg] from unification to the rise of the Third Reich, where should historians look instead? Over the last few years, the answer, it has become increasingly clear, can be found only by expanding our vision and viewing German history not in a domestic context or even a European one, but in the context of global and above all colonial developments in the Victorian era and after. This view of German history [...] has thrown up many vital new interpretations and generated a growing quantity of significant research that links Germany’s relation to the world in the 19th-century with its attempt under the Nazis to dominate it. Now this research has been brought together in Nazi Empire (2010), a powerful and persuasive new synthesis by Shelley Baranowski [...].

Baranowski’s story begins in the mid-1880s, when Bismarck reluctantly agreed to the establishment of colonial protectorates in order to win the support of National Liberals and Free Conservatives in the Reichstag. Bismarck was wary of the financial and political commitment involved in full colonisation, but he was soon outflanked by imperialist enthusiasts, merchants and adventurers, and by 1890, when he was forced out of office, Germany had a fully fledged overseas empire. It was, admittedly, not much to write home about. The ‘scramble for Africa’ had left the Reich with little more than leftovers after the British and the French had taken their share [...]. A younger generation of nationalists, who did not share Bismarck’s sense of the precariousness of the newly created Reich, complained it was an empire [...] hardly worthy of a major European power.

Evans, Richard J: The Third Reich in History and Memory. Little, Brown Book Group. Kindle Edition.

It is to Hoyer's credit that this summary of Baranowski could just as equally have been a summary of Blood and Iron, built around the same modern consensus favouring a non-Sonderweg approach to German history.

What

distinguishes Hoyer is that she belongs to a younger generation of

historians for whom a post-Sonderweg perspective of German history comes

perfectly naturally and who just accepts it as the uncontroversial norm. Nor is there any need felt to spin the Weberian prayer-wheel with

Bismarck, in order to suggest he misused his demonic charisma to lure Germany

down its fateful trajectory to the Dark Side. And nor is there any other need

for lengthy and self-conscious intellectual justifications of the kind found in early pioneers. She feels liberated from

the burdens of old-school German exceptionalism and simply gets on with

the task of showing how the modern approach is far more enlightening of

history. And get on with it she does, with breathtaking aplomb and charm, and a sparklingly captivating narrative that belies the immense complexities of the issues underlying them.

This once more takes me back to what drew me to this book. It was this excerpt on the Amazon website of this review by British historian, Andrew Roberts:

Katja Hoyer’s well-researched and well-written book is the best biography of the Second Reich in years. She cogently argues that what started in Versailles’ Hall of Mirrors need not have ended in the disaster of the Great War, and rightly rescues Bismarck from the ignominy of being a forerunner of Hitler. It will undoubtedly become the essential account of this vitally important part of European history

Andrew Roberts, author of Churchill: Walking with Destiny

I thought that was a very succinct summary of the situation and note too it was written by a British historian and Churchill biographer. Or to put it another way, historians no longer think that the rise of National Socialism had predominantly 19th-century origins. Nor did German unification in 1871 create a providential path that had no other possible outcome other than the calamities of the twentieth-century. If there is any residue of any continuity (a longue durée) left between 19th-20th century Germany, then it is only a weak secondary order of continuity in an international colonialist-imperialist structural context. Any attempt to draw the attention back to the peculiarities of 19th-century Germany in the hunt for the origins of National Socialism ends up in Sonderweg territory of a kind that imagines supposedly obvious "proto-Nazisms" in just about anything.

Hoyer rightly depicts a Bismarck who followed the principle that conservatives must make revolution on their own terms if they are to avoid having revolution forced upon them in terms unacceptable to them. Adam Tooze put up a Bismarck quote in his PowerPoint lecture slides on his website that went: “If there is going to be revolution, it would be better to make it than to suffer it”, attributed to "Bismarck 1866" but alas without a primary source citation. Following precisely that principle (similarly, Benjamin Disraeli's expressed preference for "reform from above" over "revolution from below") of revolution from above, Bismarck brought about the first German national union in 1871, creating a parliamentary monarchy with a vague semblance to the democracy that revolutionaries in 1848 had once demanded. However, the voting system contained an inherent bias towards the conservative landowners that continuously marginalised a growing left-wing labour-based movement.

From the perspective of the international order, Bismarck locked the new united Germany into a series of treatises that neutralised military threats to its precarious fledgling sovereignty. Bismarck evinced no overarching ambition for large-scale colonialist-imperialist expansionism, nor was there any practical reason to pursue such a policy. The idea that German history followed a centuries-old conspiratorial Master Plan for world-domination and genocide, making the atrocities of Hitler's regime a pre-ordained inevitability, is just far too simplistic. There is simply no way that one can prove that events of the 19th-century rendered such an outcome a grand metaphysical inevitability. Nor can such a diabolical Master Plan for World War and genocide be discerned in those who immediately succeeded Bismarck as German Chancellor and whose careers are also covered in this book. When Bismarck's system of checks and balances were inadvertently permitted to lapse, the unintended consequence was a political destabilisation that led to an ill-foreseen lurch of the power-wielding sleepwalkers of Europe into the abyss of World War I.

Only with the rise of European colonialist-imperialism accompanied by the growth of the German economy, that rapidly went through industrialisation in the late 19th-century, did the newcomer Germany start to clash with the established colonial super-powers of Britain and France. This lead to a so-call Thucydides clash between the incumbent British Empire and the upcoming German Empire around the turn of the century. But only after Bismarck's death in 1898, did a more aggressive brand of a German imperialism resentful of its playing second or third fiddle to colonialist rivals emerge, and even then not because Luther, Frederick the Great, Hegel, Wagner or Bismarck commanded it be so in exerting their diabolical charismatic influence on history from beyond the grave, but due to the structural circumstances engendered by the escalating tensions from European colonialist-imperialist geopolitical rivalries. These seething imperialist rivalries and geopolitical tensions nestled in a rapidly changing world would soon snowball into World War I.

Once again, this brings me back to what led me to this book in the first place. I am doing research into a book on Wagner, who is an important cultural figure in the historical era of the Bismarckian Kaiserreich. If Bismarck, who held high political office, is not Hitler's immediate predecessor—a figure who paved the path to the inexorable rise of the National Socialist regime—then it is scarcely plausible that an opera composer of the same era, who never once held political office, could have exerted greater influence over the course of German history going into the next century than Bismarck did. There will naturally be those who insist that writing operas gave Wagner magical power over the course of world history, of a kind denied to Bismarck, but that is most improbable without spinning the Weberian prayer-wheel in imputing that Wagner used his evil powers of musical composition to exert malign influence over the course of world history. It is just a touch too speculative in the way it exaggerates the amount of influence a mere composer could possibly wield over history. However, hammy accounts vilifying Wagner as a kind of Voldemort-like Dark Lord, using his diabolical charisma to lure Germany down the path of its Sonderweg remain amusingly popular.

Much to Hoyer's credit, the post-Sonderweg approach naturally leads to an avoidance of Luther-to-Hitler, Hegel-to-Hitler, Wagner-to-Hitler, or for that matter, Bismarck-to-Hitler varieties of gross reductivism. Avoidance of the Sonderweg thesis seems to result in an alleviation of any demonic urge to find evidence of the all-pervasiveness of "proto-Nazism" in Bismarckian Germany, one where:

Genocide was immanent in the conversation of German society. It was immanent in its language and emotion. It was immanent in the structure of cognition.

Daniel Goldhagen: Hitler’s Willing Executioners, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1996, p. 449

Freed of the burdens of the Sonderweg, Wagner's primary bibliographic source texts can suddenly be read for what they are worth. That is why Hoyer feels no need to airbrush those passages in Wagner's "What is German?" (1865/78) from history, where he expresses profound disillusionment at the newly united Germany created by Bismarck, due to the downtrodden status of a heavily exploited working class on the backdrop of a German industrial revolution: "the workman hungers, and industry has fallen sick [the economy fell into recession in 1873]", wrote Wagner. In Bismarck's new Germany, Wagner complained about "feeling odd in this new 'Reich'" and when castigated that he "must not consider" himself "sole lessee of the German spirit" Wagner wrote "I took the hint, and surrendered the lease". So out of place (sonderbar) did he feel that (not mentioned in Hoyer's book) Wagner tried to emigrate to America like thousands of other German workers. For once, Wagner's primary bibliographic source references are allowed to speak for themselves, something vanishingly rare in Wagner studies. Nor does Hoyer feel the need to airbrush from history the simple fact that Wagner had fought behind the barricades in 1849, musket and grenade in hand, to defend the cause of a fledgling German democracy.

Like many '48ers, Wagner had initially supported Bismarck's unification drive around the time of the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) as it bore a tantalising resemblance to the demands for a democratic united Germany they had made back in 1848. Even Marx and Engels acknowledged Prussia's right to wage a defensive war. After all the incumbent military superpower of France under Emperor Napoleon III had initiated hostilities first by declaring war against the underdog Prussia. Historian Jürgen Tampke paraphrases Han-Ulrich Wehler:

Unification brought about by victory over France...led to an unparalleled level of national celebration and enthusiasm. According to a leading German historian [Hans-Ulrich Wehler, in his Deutsche Gesellschaftsgeschichte], the Bildungsbürgertum (educated bourgeoisie)—academics, lawyers ... and other university-educated citizens—had been elevated into a ‘highly emotional state of euphoria’. German liberals who, ten years earlier, had seen Bismarck as their arch-foe, the reactionary personification of Prussian conservatism, now faced about: for the first decades of the new German empire, they became his firmest supporters in the Reichstag.

Tampke, Jürgen. A Perfidious Distortion of History: the Versailles Peace Treaty and the success of the Nazis. Scribe Publications Pty Ltd. Kindle Edition.

Dr Förster sent us an invitation for the founding of an antisemitic newspaper. R[ichard] recalled that he had written to him from Naples:

“You should take a look to see if you fit in Prince Bismarck’s trash [Kram], and it looks like you fit into the trash, because you’ve adopted his entire programme. It looks like we Bayreuthers with our ideals are going to be very isolated”.

Dr. Förster schickte ihn einen Aufruf zur Gründung einer anti-semitischen Zeitung. R erzählt, daß er von Neapel aus ihm geschrieben zu haben:

»Sehen Sie, ob Sie in Fürst Bismarcks Kram passen und Sie scheinen in den Kram zu passen«, —und Sie scheinen in den Kram zu passen, denn Sie adoptieren sein ganzes Programm. »Wir Bayreuther mit unseren Ideen werden sehr einsam bleiben”.«

Cosima Tagebuch: p672 Sonnenabend 22ten Januar 1881. My own translation.

Note that in Stefan Breuer's book, Die Völkischen in Deutschland, on the history of the völkisch movement, much praised by Geoff Eley and hailed by Hans Mommsen as the standard reference text on the subject, he also acknowledges Wagner's contempt towards them and quotes this same passage. Nor must it be said was the Bismarckian era German regime a völkisch one. Wagner is simply being polemical when he imputes that Bismarck belongs in the same rubbish bin as the fringe early völkisch movement.

So what then of the "infamous antisemitic polemic", which Hoyer still attributes in one passage to Wagner? One quibble I have with it is that historians of the Shoah prefer to distinguish between different types of antisemitism. Holocaust historian (and Holocaust survivor), Professor Saul Friedländer, supports the interpretation that Wagner's views on ethnicity represent a left-wing revolutionary strand of thought identical to that found in Karl Marx. The essay On the Jewish Question (Zur Judenfrage) was published by Marx in 1844, at much the same time as Wagner's own 1850 Communist period essay on the Judenfrage or Jewish Question.

For those unaccustomed to thinking of Wagner as a Communist, in 1850 he also wrote of revolution as the "passing over of Egoism into Communism" (The Artwork of the Future). Wagner always uses the term "Egoism" in place of "Capitalism". Around the time of the Paris Commune, 1871, Wagner wrote a new preface to this work, in which he reiterated that: "I do not deny ... that Communism is the antithesis of Egoism". Strange though it may seem, Wagner was as much a thinker of The German Ideology as Marx was.

| Wagner saw the end of capitalism as the "passing over of Egoism into Communism" (from Das Kunstwerk der Zukunft, 1850) |

Only the Communist Wagner goes further than the Communist Marx in making it clear that he did not condone "Medieval Jew-hatred" and making it explicit that he advocated for the "assimilation" of the Jews, calling upon Jews and Gentiles to become "united and undifferentiated".

| Wagner explicitly disassociated himself from "tendencies towards Medieval Jew-hatred": "mittelalterlichen Judenhaß-Tendenz". |

| Wagner called upon Jews and Gentiles to become "united and undifferentiated" (einig und ununterschieden") through assimilation |

While assimilationism is no longer considered compatible with our 21st-century post-Shoah views on ethnicity, it once represented a liberal and revolutionary view relative to the time, and one advocated for a long time by Theodor Herzl—a Wagnerian and the father of Zionism. Not only that, but in 1850, Wagner even stated he had nothing against the idea of the creation of a Jewish state (ein jerusalemisches Reich) i.e. Wagner supported the idea of Zionism half a century before Herzl's 1896 publication of Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State), the founding article of Zionism, subtitled by Herzl "Versuch einer modernen Lösung der Judenfrage" (an attempt at a modern solution to the Jewish question). It is potentially misleading for authors to write about Wagner's "infamous antisemitism" without qualification, as it tends to encourage the Wagner-to-Hitler Sonderweg thesis locating the origins of National Socialism out of a pervasively proto-Nazi 19th-century German culture. It is thus just as misleading to talk of the "infamously antisemitic polemicist, Wagner" as it is to talk of the "infamously antisemitic polemicist, Marx". A Wagnerian like Theodor Herzl in 1896 would most likely have found Wagner's essay on the Jewish question more progressive, modern, and enlightening than the one by Marx who lights no path to salvation for Jews, condemned as capitalist "hucksters" who worship money as the jealous God of Israel.

Further unexpectedly illuminating of Wagner's later political thought, once the Communist revolutionary fervour cooled down in the decades after the 1848 Revolutions, is Hoyer's explanation of the pre-unification customs union (Zollverein) among the splintered German nations. Although not discussed in the Hoyer book, after becoming disillusioned with Bismarck, Wagner came to advocate later in his life for Young Hegelian thinker, Constantin Frantz. With Wagner living in Bavaria and patronised by the Bavarian King Ludwig, Wagner became sympathetic towards the dissolution of the 1871 German union and Bavarian succession out of its national union governed from Berlin, the heart of Prussia.

Hoyer's insights into the pre-history of German unification helps us to illuminate the political theories of Frantz, as articulated by him in his Open Letter to Richard Wagner written in response to the essay "What is German?" that Hoyer touches on. This can now be read as advocating a return to a customs union, the Zollverein. Only this was much more radically accompanied by the formation of a Central European federal government, with a constitution based on that of the United States of America:

There will be no remedy except through that of a European Federal system, one that itself can never come into existence again, unless it arises from Germany, in which it reflects to a certain extent the different European nations and its various original peoples, in which Germany is, as though prefigured from the outset, for the Federation. If these natural arrangements were further developed, the German Constitution will be related in this regard to the North American, and we will be able to gleam the typical expression of the New World again in North America, so that ... Germany too receptively accords to the life forms of the New World. ... Through Germany Europe has fallen, through Germany it must rise again.

Constantin Frantz: Open Letter to Richard Wagner, Bayreuther Blätter, June 1878 (written on invitation in response to Wagner's "What is German?", 1878). Full original German text of Offener Brief an Richard Wagner posted here

Regions like Bavaria would undergo succession out of the 1871 German national union, into the economic union of a federal Zollverein. Into this, nations like Poland would also be able to belong. It is effectively a theoretical prototype for the European Union. Even today the EU threatens classical national unities, with ethno-socially distinct regions like Scotland threatening succession out of British union, in favour of union with the "Zollverein" of the EU. A similar situation exists for the Catalan succession movement in Spain. Only with Frantz and Wagner, the concept was applied to Bavaria, which later did attempt succession out of the German union with the declaration of a Bavarian Soviet during the German Revolution of 1918-1919. Just like the attitude of the Irish or the Scots towards London, and Catalans towards Madrid, Bavarians have often felt uncomfortable being part of a national union dominated by Berlin. Wagner and Frantz argued that permitting regional independence (while being allowed to join a federal union) did greater justice to the cultural diversity found in German-speaking lands, as throughout Europe. Wagner's acceptance of Zionism is just another extension of this concept, as is the Pan-Slavic movement Bakunin had been part of just before joining Wagner in the 1849 Dresden uprising.

Hoyer's book also makes it clear how unrealistic a pipe dream these alternative visions were of "what Germany is" relative to the political actualities of the era with the fall of the German Bund due to Austro-German tensions and the geopolitics of the European scene. The pragmatic politics of the Bismarckian version of Realpolitik ended up creating a quite different solution. That is something Frantz and Wagner knew in calling their prototype of the EU, "Metapolitics", the political dreamers' equivalent of metaphysics, contrasting with the brutally pragmatic Realpolitik of the era. You may laugh and call us dreamers, warns Frantz in his Open Letter to Richard Wagner, but with the growth of a military industrial complex and escalating geopolitical tensions, wars like the Thirty-Year War and the Napoleonic War may yet recur—history will judge who was the sleepwalker and who the nightwatchman.

Hoyer is to be further praised for not only recognising the inherent changes in policy from different generations of German Chancellor from Bismarck onwards, amid ever-changing geopolitical structural circumstances, but she implicitly recognises institutional change within the cultural institution of Bayreuth from between Wagner's time and that of his successors. Hoyer recognises that once the baton of leadership at Bayreuth had been passed on from the "Meister" (Wagner) to his second wife, Meisterin Cosima, that a regime change had occurred. Cosima (1837-1930) outlived Wagner (born 1813: old enough to be his second wife's father) by some half a century, during which time the changes in Bayreuth mirrored the equally profound changes in the structure of German society. Just as the institution of Chancellery changed, so too did the institutional leadership in Bayreuth change with history. The result was historical discontinuity.

The Bayreuth after Wagner's death that courted first Kaiser Wilhelm II, and later Hitler, was no longer one that rejected the völkisch movement with abject contempt, but one that openly embraced it. Just as there was no grand sweep of a singular path of fatal continuity in the office of Chancellery between Chancellor Bismark's time to that of Chancellor Hitler, there was likewise no grand continuity between Bayreuth in the time of the Bayreuth Meister to that of his successors, Meisterin Cosima or Winifred. Instead of such fatal straight lines, there are only "twisted roads" and endless nonlinear discontinuities. History is just never that simple.

Thus, Hoyer makes no attempt to draw straight lines of continuity between Wagner's thinking and that of the Aryan supremacist ideologue, Houston Chamberlain, a popular author during the Wilhelmine Kaiserreich. The syphilitic Chamberlain was made Wagner's son-in-law by the pious Cosima as a means of anointing Chamberlain's racist ideology with the Wagner family seal of approval. The reality was that Wagner died without knowing who Chamberlain was, having never met him.

Oliver Hilmes summarises the völkisch Wagner cult of the Wilhelmine era well in his Cosima biography:

There is no doubt that without Cosima and her accomplices, the occasionally bizarre cult of Wagner in Wilhelminian Germany might have petered out in the sands of insignificance, but instead they jointly succeeded in transforming the spirit of Bayreuth into a national and nationalist ‘cause’. It was Cosima’s charisma as the legitimate ‘guardian of the Grail’, her organizational skill and her ideological obstinacy that enabled Bayreuth to prove so disastrously effective as a [völkisch] political force in Germany.

HILMES, Oliver. Cosima Wagner: The Lady of Bayreuth. Yale University Press. Kindle Edition.

One is bound to ask if all this was really undertaken ‘in the spirit of Richard Wagner’. And the answer is that this seems unlikely. In his disciples’ hands, Wagner’s ideas degenerated to the level of a muddy and vulgar ideology that hailed a chauvinistic art out of touch with the real world as if it were a substitute religion.

HILMES, Oliver. Cosima Wagner: The Lady of Bayreuth. Yale University Press. Kindle Edition.

A reading of Hoyer's book shows how this völkisch Wagner cult was the historical by-product of Cosima and Chamberlain's structural milieu in Wilhelmine Germany. But there was no straight line of continuity between that time and that of Wagner and Bismarck before it. And as Thomas Weber has shown in his Becoming Hitler, there is not even a straight line of ideological continuity passing from Chamberlain to Hitler, between whom a yawning gulf still existed. There is no Sonderweg.

...the radical liberalism of [Wagner's] early years was airbrushed out of existence in his disciples’ picture of their hero. Or, to put it another way, Wagner was robbed of his own biography and brought into line. And all of this was done with constant appeals to the dead Master, who could no longer defend himself against such an act of wholesale misappropriation.

HILMES, Oliver. Cosima Wagner: The Lady of Bayreuth. Yale University Press. Kindle Edition.

There is one last minor quibble left to mention and that is the way Karl Marx is portrayed as a political "extremist". More recent rereading of Marx shows that he expended much effort in the 1870s to undermine attempts by Wagner's old friend from 1848, Michael Bakunin, from pushing the International in the direction of conspiratorial revolutionary activism. Instead, Marx rejected insurrectionary secret societies in favour of open political parties.

There is an argument that the late Marx conceded to the Realpolitik (Hoyer teaches us that it originally meant the post-utopian politics of moderates striving for realistic incremental progress) of the post-1848 world to become more of an incrementalist Social Democrat than an insurrectionary Communist. The conspiratorial extremist Marx of legend is mostly a mythical by-product of 20th-century historical calamities, in a similar vein to the mythical völkisch Wagner. Thus, key events of the 20th-century were not caused by ideological missteps of '48ers disillusioned with the failure of the 1848 Revolution—with Stalin acting under orders from '48er Marx to create gulags, and Hitler acting under orders from '48er Wagner to create concentration camps. Once again, there is no Sonderweg—nor any other simple straight line—leading fatalistically from the 19th-century to the unprecedented calamities of the 20th-century. It is time we stopped trying to pin the blame for the 20th-century onto the 19th-century. Hoyer's book, Blood and Iron, nonetheless goes a long way towards showing us why.

In conclusion, Katja Hoyer cannot be commended enough for communicating the intricacies of these "twisted roads" of history with effortless aplomb. It reminds me of the saying that "if you cannot explain something simply, you do not understand it well enough". The counterfoil to this is that "everything should be made as simple as possible but not simpler" and that too is achieved. This is a book whose seeming crystalline clarity and deceptive simplicity utterly belie the nuanced complexities it communicates with such unforced eloquence. Even more importantly perhaps is that she deftly navigates the middle path of indifferent neutrality between the twin perils of apologia and finger-pointing accusation. Highly recommended.

No comments:

Post a Comment